Atrial fibrillation (AFib) and heart failure are two of the most common heart diseases. What’s fascinating is that the two frequently coexist. As many as half of patients with newly diagnosed heart failure are also found to have AFib, and close to a third of patients with new AFib diagnoses have heart failure.

The most recent data from 2017 indicate that nearly 6 million people in the U.S. have heart failure and another 6.1 million have AFib. These high patient volumes indicate that doctors and patients must become more aggressive in therapies, particularly when patients have both conditions. No large studies to date have uncovered treatments that effectively manage the symptoms and increase survival rates of both diseases when they occur simultaneously. While beta blockers and ACE inhibitors are effective for heart failure, most research has focused on heart failure treatment without addressing the overlapping AFib.

However, new findings published in The New England Journal of Medicine indicate that catheter ablation therapy has the potential to do both. “Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation with Heart Failure” is the first study to measure the effectiveness of the procedure on both diseases, and the data likely will change the way we approach treatment of these patients.

How catheter ablation improves AFib in heart failure patients

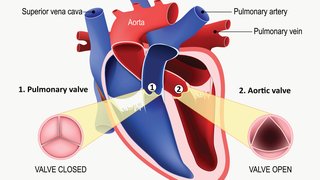

The goal of cardiac catheter ablation is to locate and ablate, or destroy, abnormal heart tissue that’s causing a patient’s abnormal rhythm. Stopping the AFib typically helps patients with heart failure feel better in general; increases survival rates; reduces hospitalizations for heart failure, and improves heart function allowing for better exercise tolerance.

Cardiac catheter ablation is a minimally invasive procedure. The patient is put under general anesthesia and the doctor inserts thin, flexible tubes called catheters through the femoral vein in the leg. We map the heart with low-radiation imaging techniques to locate the abnormal tissue. Then we use tools inserted through the catheter to ablate the tissue.

The procedure takes three to five hours, which is much less time than it used to require. As with all procedures, there is some risk, though it’s minimal. Major risks such as stroke or bleeding around the heart occur in fewer than 1 percent of patients. Bleeding in the catheter insertion point in the groin occurs in approximately 5 to 7 percent of patients.

The doctor and patient should discuss whether the risks outweigh the benefits of the surgery. The best candidates for cardiac catheter ablation:

- Are generally healthy aside from having heart failure

- Have recently diagnosed atrial fibrillation

- Have episodes of AFib rather than continuous rhythm problems

What patients should expect as a result of this study

Doctors and patients should collaborate to become more aggressive in treating AFib in patients with heart failure. We must have thorough conversations about risks, benefits, and candidacy for the procedure to extend more lives and improve patients’ quality of life.

Patients should feel confident asking their cardiologists questions about cardiac catheter ablation. And if the cardiologist thinks the patient could benefit – or would like to consult with an AFib and heart failure specialist – the doctor can refer the patient to a high-volume heart center such as UT Southwestern. All patients in the landmark trial were treated at high-volume centers, and study after study have shown that high-volume centers typically have the best patient outcomes.

If you’re interested in discussing cardiac catheter ablation for AFib with heart failure, call 214-645-8000 or request an appointment online.