Sometimes even physicians do things because they’ve always been done that way.

That’s what we’re seeing with how we measure fitness. Research we recently completed suggests we're due for a broader definition of fitness improvement.

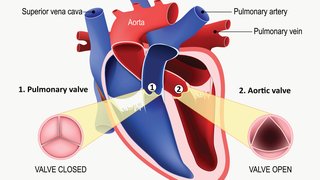

We have long defined improved fitness as improved cardiorespiratory fitness – the ability of the cardiovascular system to supply oxygen to the body. Most people who exercise regularly show clear improvements in their cardiorespiratory fitness. The more they train, the better their ability to transport oxygen.

But about 30 percent of people who exercise are considered exercise “nonresponders.” Despite their exercise efforts, their ability to transport oxygen never improves. Thus, under the current definition, their fitness does not improve.

The study my colleagues and I recently completed suggests we need to broaden our definition of what it means to improve fitness. This is particularly important for people with diabetes.

Exercise ‘nonresponders’ can improve fitness

We looked at the effects of exercise on people with Type 2 diabetes – one of the leading risk factors for heart disease. Some of the people in the study participated in aerobic exercise, some did resistance training, and some did a combination of the two.

We saw significant improvement to metabolic measurements, both in those who improved their cardiorespiratory fitness and in those who didn’t. Our study showed that by exercising, participants improved their blood glucose levels, A1c levels (a long-term measurement of high blood sugar), waist circumferences, body fat percentages, and BMI (body mass index), even if their cardiorespiratory fitness did not improve.

Our findings suggest that our definition of an exercise “nonresponder” is too narrow. Individuals can improve their diabetes control with exercise even if they do not improve their traditional measures of cardiorespiratory fitness. Said another way, we need to broaden our understanding of “response” to exercise so that we consider all of the potential benefits of exercise training—both the cardiovascular benefits and the non-cardiovascular, metabolic benefits.

As a preventive cardiologist, I always urge my patients to follow a regular exercise program. The findings of this study have given me more reason to exercise, too. Not only can exercise improve heart health, but for those who have diabetes, it just might help improve their diabetes, too.