Generations of men underwent prostate cancer tests during an aggressive screening regimen. Then, the screenings stopped. Now doctors are reevaluating just how worried men should be about their prostate.

by Michael J. Mooney

It’s tucked deep within the body, nestled between the bladder and penis, an elusive gland roughly the size of a Ping-Pong ball. Many people don’t know what, if any, purpose the prostate serves — most of what we hear about it revolves around the problems it can cause, especially later in life. But without it, there might not be any life at all.

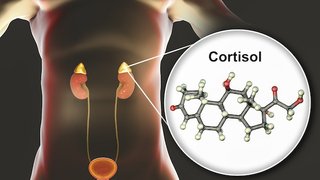

In some ways, the male prostate gland is equivalent to the female mammary glands. Mammary glands are responsible for nourishing a child in the early stages of life; the prostate is responsible for protecting the sperm even earlier. It does this by producing an enzyme called prostate-specific antigen (PSA), which liquefies the semen, essentially freeing it from the seminal coagulum. PSA also gets credit for neutralizing the cervix’s blocking enzyme, which allows sperm to freely enter the uterus and, hopefully, penetrate the egg.

“The prostate gland, small as it is, is like a multifaceted diamond: every time you look at it from a different angle, under a different light, you see a different aspect of it, find a new scientific challenge, unresolved mysteries,” says urologist Dr. Claus Roehrborn, who specializes in prostate diseases and has chaired the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Department of Urology since 2002. His work is at the forefront of current innovations in treating and diagnosing prostate cancer.

The gland — which also helps control the flow of urine and produces ejaculate fluid — averages about 30 grams in size in adult men, and is usually smaller in younger men (think about the size of a walnut) and larger in older men (anywhere from the size of a Ping-Pong ball to a tennis ball).

Size Matters

The prostate gland tends to grow as men age.

Younger Men

On average, the prostate is about the size of a walnut.

As Men Age

It grows to roughly the size of a Ping-Pong ball, weighing 30 to 35 grams.

Older Men

In many men, it continues to grow even further, to the size of a tennis ball or larger.

As men age and their prostate grows, they become more susceptible to two conditions: prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Though both conditions are rare in men younger than 40 years old, they become increasingly more common with every decade that passes.

At the age of 50, a man’s risk of BPH is roughly 50 percent. By the time he’s 80, his risk will have increased to nearly 90 percent. The gradual growth in prostate size eventually causes the gland to put pressure on the urethra, which makes the bladder have to work harder. Symptoms of BPH include incontinence, difficulty urinating, and frequent urination. Doctors don’t agree on what precisely causes BPH, but common theories relate to the changing levels of testosterone present in the body as it ages. And though BPH can be annoying and uncomfortable and, on rare occasions, require surgery, it’s not particularly dangerous.

The other condition — prostate cancer — can be much more threatening. It’s the most common kind of cancer found in males, and the second most fatal (after lung cancer). The lifetime rate of prostate cancer is about 1 in 9, and about 1 in 41 men die from it. The American Cancer Society predicts that there will be about 165,000 new cases of prostate cancer this year. Unlike breast cancer, which attacks women of all ages, prostate cancer is exceptionally rare in young men; the average age of a prostate cancer patient at the time of diagnosis is 66 years old.

As with all cancers, prostate cancer occurs when cells within the gland begin to grow out of control. Some prostate cancers remain inside the prostate. Some are slow-growing and very low-risk. Others are more aggressive, spreading to neighboring organs of the body or metastasizing in the bones.

Because the prostate is so neatly hidden behind other organs, and because BPH and prostate cancer often have many of the same initial symptoms, making an accurate diagnosis has proven difficult.

The story of how science has evolved over the last half-century — how doctors have struggled to figure out who has prostate cancer and how to responsibly screen for it — is a fascinating tale of ingenuity, innovation, and groundbreaking revelations about human nature.

“The prostate gland is like a multifaceted diamond: every time you look at it from a different angle, under a different light, you see a different aspect of it, find a new scientific challenge, unresolved mysteries.”

Dr. Claus Roehrborn

Dr. Roehrborn’s office is off the middle of a long hallway, eight floors up, tucked away somewhere in the maze of buildings at UT Southwestern.

The room is narrow and the walls are covered with informational posters, with a shelf full of plants by the window. There’s a small table for meetings near the door, and beside that sits a magazine rack bursting with medical journals and all the latest studies in urology.

Roehrborn is well-groomed and serious, and his voice carries the lilt of his native Germany. He’s published hundreds of papers on the subject of prostate cancer and performed thousands of various prostate-related surgeries. When he talks about prostate health, it’s clear that he sees a grand scope to his work. Effective testing for prostate cancer means, in no uncertain terms, extending the life expectancy of humanity.

The doctor was born in 1956 in Bottrop, a midsize industrial city in West Germany, about an hour north of Cologne. His father was a teenager during World War II and was drafted out of high school to work as an antiaircraft gunner. When the war ended, he worked as a laborer and earned his high school equivalency at night. Growing up, Roehrborn’s family was middle class, but his parents put a high value on education.

“Schooling was everything,” Roehrborn says.

As Germany flourished under the Marshall Plan — the American initiative to rebuild Western Europe after World War II — Roehrborn’s parents were able to send their three sons to college, and then to medical school. Roehrborn never set out to be a urologist, but during medical school in Giessen, Germany, he connected with a doctor who deeply inspired him.

“He was the most methodical person I ever met,” Roehrborn says. “Whether it was early in the morning, late in the evening, whether he was tired or not, whether he liked them or not, everybody got the same systematic evaluation and systematic documentation.”

1950s

/ 60 Years of Prostate Cancer Discovery /

The digital rectal exam (DRE) allows doctors to physically feel for abnormalities in the prostate, but is such an undesirable method that only an estimated 1 in 10 men opt to have the test. This rudimentary technique is also only useful if the tumor has grown on the side of the gland accessible by the rectum; and it doesn’t tell doctors what is dangerous or worth biopsying.

This doctor, who happened to be a urologist, quickly became Roehrborn’s role model. Though he’d had no particular inclination toward urology before, Roehrborn soon decided to adopt it as his field of study. He grew to appreciate how each case presented itself like a puzzle he could piece together and solve, and he completed his internship and part of his residency at the German army hospital in Giessen.

During his residency, Roehrborn was part of a rotational program that sent residents to conduct research in America at Johns Hopkins University; the University of California, San Francisco; or

UT Southwestern. In 1984, it was his turn to be sent overseas, and he wound up in Dallas, during a particularly sweltering Texas summer.

Though Dallas’s summer heat was like nothing he’d known in Germany, he adjusted quickly. At the end of his one-year term, the department chair asked if he’d stay for another year and he agreed. At the end of that year, the chair asked if he’d like to do his whole residency at UT Southwestern. Again he agreed — and then stayed on as a fellow.

Rooting his four-decade career in Dallas was an accident, Roehrborn says. “It was not planned that way.”

Now he’s considered one of the foremost experts on this peculiar and potentially dangerous gland. His career has run parallel to some of the most important evolutions in prostate cancer detection, and his work has changed the field immeasurably. He’s also emerged as a moderate voice of reason in what has become an especially contentious international debate over medical policy.

1980s

/ 60 Years of Prostate Cancer Discovery /

It is not uncommon to see patients brought in on a stretcher, paralyzed from prostate cancer that has metastasized to the spine. Obviously, the cancer is going unchecked and tests aren’t doing enough to prevent fatalities.

Fifty years ago, men were dying and no one knew why.

Prostate cancer is often slow-growing and can progress without symptoms for long periods of time. So for centuries, by the time someone discovered the cancer, it had often already spread — to the lymph nodes, bones, to any number of other organs. It didn’t help, either, that prostate cancer and its less threatening counterpart, BPH, share many of the same symptoms — weak urine stream, blood in the urine, frequent urination — making the cancer nearly impossible to diagnose on indicators alone.

By the middle of the last century, the dreaded digital rectal exam (DRE) — one of the most notorious and joked-about examinations in the history of medicine — had been developed as a way for doctors to physically feel for potential abnormalities. If you’re not familiar with the specifics of the DRE, “digital” refers to fingers and ... you can figure out the rest on your own.

Though this test made it easier for doctors to locate tumors that had grown in specific areas of the gland, it wasn’t without serious limitations. A doctor could use the DRE to feel for abnormalities on the prostate, but only on one side of it. If a tumor was growing on a side not accessible through the rectum, it would be missed entirely and left to spread unchecked. Relying on touch to identify growths on a man’s prostate was a helpful step forward, but the DRE was still a rudimentary technique. It allowed doctors to detect that something was there, but didn’t do much beyond that to determine what, precisely, that something was. That’s important, because there are several different kinds of prostate cancers and not all of them are considered dangerous or worth biopsying.

Also, not loving the idea of a doctor inserting a finger into their respective rectums, a large percentage of men dreaded or permanently put off having the test.

An estimate from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services says that only 1 in 10 men who should be receiving a rectal exam actually get it.

During his residency in the mid- to late 1980s, Roehrborn saw a patient at least once a week who was brought in on a stretcher, paralyzed. It wasn’t because the patient had broken his back; it was because he had prostate cancer, and it had spread, eating into his spine, collapsing it, and compressing the nerves.

“Coming in paralyzed from a prostate cancer metastasis to the spine was actually a common first diagnosis in my residency,” Roehrborn says. “You would put your finger in the rectum and there was a stone right on the prostate. You’d put two and two together, do a bone scan, and see the guy is loaded with metastasis.”

Since prostate cancer forms on a hidden organ and can be confused for a benign and fairly common condition, it’s hard to predict who’s at risk. A man’s behavior seems to have little effect on whether he’ll develop it, with no studies showing strong links between the cancer and eating certain kinds of food, smoking, or drinking alcohol. And for the most common types of prostate cancer, family history doesn’t seem to play much of a role, either.

But still, if prostate cancer is caught while it’s still local — when it hasn’t spread to other parts of the body — survival rates are nearly 100 percent. Doctors knew there had to be a better way. A way to detect the tumor faster, more definitively, and less invasively.

By the Numbers

1 in 9 men develop prostate cancer.

1 in 41 men die from prostate cancer.

165,000 new cases of prostate cancer are predicted this year.

66 years old is the average age of diagnosis.

40-80 years old is when most men have biopsies performed.

1986

/ 60 Years of Prostate Cancer Discovery /

The FDA approves a blood test after scientists discover that high PSA levels in the blood could indicate prostate cancer. However, the test does not differentiate between dangerous cancers, nonthreatening tumors, BPH, prostatitis, and simply old age — all of which could cause elevated levels of PSA. Suddenly, there’s an apparent prostate cancer epidemic; urologists are performing a million invasive biopsies a year, to varying results.

As Roehrborn was just beginning his career, a new test emerged.

A team of scientists at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, New York, had set out to find a way to detect prostate cancer with a simple blood test. The hope was to uncover a certain protein marker that could be linked back to cancer and used as a definitive indicator. After thousands of tests, they finally made a breakthrough, and published their findings in a 1979 edition of The Journal of Urology.

What the Roswell researchers had discovered was that PSA — the enzyme that helps liquefy sperm — was found not only in the prostate, but in small amounts in a man’s blood. And, the higher the amount of PSA in the blood, the more likely a man had prostate cancer.

The ability to check PSA with a blood test was a breakthrough, and the FDA approved the procedure in 1986. It was quick, easy, and noninvasive, and certainly provided a less-embarrassing alternative for men who’d previously been dodging the DRE.

Still, it wasn’t foolproof. Generally, the larger the prostate, the higher the level of PSA in the blood. High PSA levels could, in fact, point to prostate cancer, but there were plenty of other factors that could increase PSA: BPH and prostatitis, an inflammation of the prostate, both cause elevated levels, and levels are thought to increase as a person ages, too. And, again, some types of prostate cancer are slow-growing to the point of harmlessness, meaning that their rate of growth is so glacial that the afflicted person will almost certainly die from something else — maybe old age — before the cancer grows enough to be harmful. For those cases, treatment also hurts more than it helps.

So, one major problem with the PSA test was that it couldn’t differentiate among bad cancer, “good” cancer, or other prostate conditions. And as it was integrated into mainstream medical procedure, something unexpected happened: Doctors discovered a prostate cancer epidemic. Men were suddenly being diagnosed with prostate cancer by the hundreds of thousands.

Roehrborn compares it with testing for diabetes in a medieval village. “Because you’re looking for something nobody was previously looking for,” he says, “you’re likely to find what looks like an epidemic.”

If a man’s PSA blood test level came back high, the next step was to perform a biopsy, a process that involves the patient taking an antibiotic, getting an enema, and having an ultrasound probe inserted in the rectum. Using ultrasound guidance, a needle is passed through the rectal wall into the prostate, and from there, sample snippets are retrieved.

1993

/ 60 Years of Prostate Cancer Discovery /

The U.S. initiates one of the largest screening studies ever conducted in America. Subjects are randomized to either receive or not receive PSA screenings in an attempt to determine the merit of the screenings.

The new procedure, it turned out, was much more complicated and invasive than the DRE, and there are plenty of associated risks. Besides general bleeding, including blood in the urine, stool, and semen, there might be bacteria in the rectum that the needle could drag into the bloodstream. This can cause infections, and some patients might even wind up with sepsis.

“There’s consequences to these biopsies,” Roehrborn says. “When you do it, you say, ‘Yeah, it’s a price to pay, but is it a good trade-off?’”

At one time, he says, urologists were doing a million biopsies a year in the U.S. — a huge number, especially when you take into consideration that most biopsies aren’t performed on men under 40 or over 80. Even though there were potential side effects to biopsies, including danger and discomfort, urologists believed that they were doing the right thing. After all, they were detecting cancer early, and men’s lives were being saved.

Once cancer was detected, a sampling of cells was examined under a microscope and rated according to the Gleason grading system, designed to help inform prognosis and treatment. Using the Gleason system, doctors examine patterns present in cancerous tissue samples and assign numbers based on what they detect. The primary and secondary cell patterns are evaluated and correlated with one of five prominent prostate cancer patterns, each of which has an assigned number: 1 is fairly nonthreatening and 5 indicates the most aggressive or deadly cancer. So, if a person’s primary pattern was rated a 3, and the secondary pattern was a 4, his Gleason score would be 3 + 4, or 7.

The problem was that a lot of people who were being biopsied had low Gleason scores — meaning that their primary cancer patterns were 1s or 2s, and often required no further action. Ones and 2s are rarely used for biopsies today. At the time, though, doctors were doing too many biopsies, Roehrborn says, because they didn’t know when to do them.

“How do you biopsy only men who have the bad cancer?” Roehrborn asks. “And how do you make it so that if you do a biopsy, you have a high chance of finding a really aggressive cancer — the one you want to find?”

The PSA test had been a breakthrough, but it had triggered a tidal wave of unforeseen complications. And again, physicians on the ground, treating patients, knew there had to be a better way — one that wouldn’t result in thousands of men receiving unnecessary and uncomfortable procedures.

2009

/ 60 Years of Prostate Cancer Discovery /

The study shows that the screenings do not reduce the death rate of prostate cancer — a direct contradiction to the results of a coinciding European study, which shows that screening reduces death rates by 20 percent.

In the early 1990s, researchers initiated the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) in hopes of evaluating whether PSA testing had impacted prostate cancer death rates.

The study involved eight European countries (Sweden, the Netherlands, Finland, Italy, Belgium, Switzerland, France, and Spain), hundreds of doctors, and roughly 184,000 men between the ages of 50 and 74. The participants were randomly split into two groups. The first group was assigned to PSA testing — one test every few years (PSA tests varied in frequency among the countries; some were every year, others were every two, three, or four years). If a subject’s PSA levels went up between tests, he’d be directed to have a biopsy. The second group was told not to have regular PSA screenings.

Meanwhile, in 1993, the U.S. started a similar survey. The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial was one of the largest screening studies ever conducted in America, involving 77,000 participants. For the prostate portion of the study, patients were randomized to receive either a PSA screening once a year, or no PSA screening at all.

Most field experts expected that the two studies would produce similar conclusions. In 2009, the results of the European ERSPC study and the prostate-related data from the American PLCO study were published side by side in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The European study had found that, while there was a risk of over-diagnosis, PSA screening reduced the death rate of prostate cancer by 20 percent. The American study, though, reported that there was no significant difference between the two study groups — meaning that the risk of death was equally low for those who had received regular PSA tests and those who hadn’t.

“It was completely different from the Europeans’ [results],” Roehrborn says. “Behavior is not a factor, and where you live is not a factor. So everybody looks at these numbers and is agonizing — how is this possible? How can one group have a statistical reduction in mortality — and the other does not?”

2012

/ 60 Years of Prostate Cancer Discovery /

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force lowers its rating of PSA screening to a D, indicating that doctors should not recommend the procedure to patients. It is later discovered that 90 percent of study participants who were told not to get the PSA screening did actually get screened, rendering the study’s results wholly inaccurate.

The medical community was shocked. There were follow-up reports published on both the PLCO and ERSPC studies, but the results remained the same: The European study found that PSA testing helped prevent death; the American study found that it didn’t.

In 2012, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the government organization assigned to assess and give guidelines on preventive measures, issued a de-recommendation for PSA screening, a decree that stunned doctors. Despite the fact that death from prostate cancer in the overall population had diminished since PSA testing had been introduced, the health panel lowered its rating of the procedure to a D — a direction to doctors to not even broach the subject with their patients.

“They didn’t discuss the drop in mortality; they just said, ‘Whatever it is, we know one thing: Your PSA screening isn’t doing it,’” Roehrborn says.

More studies were published, and finally people began to ask: Did the participants in both studies actually do what they were supposed to? Could something as simple as noncompliance explain the baffling discrepancy? And if so, who wasn’t complying, the Americans or the Europeans?

After looking into it, researchers found that in the American study, the group of participants who were instructed not to get PSA tests actually did get them.

And not just a few. More than 90 percent did, which means that the study’s unfavorable findings on PSA screening weren’t just contaminated, they were wholly inaccurate.

“The benefit is that the MRI will eliminate about 30 percent of biopsies. One year we did a million biopsies in the United States. So think about a million MRIs — 300,000 men will walk home free, no biopsy.”

Dr. Claus Roehrborn

Last year, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reversed its D rating of PSA testing to a C for men ages 55 to 69, recommending that doctors at least discuss the test with their patients.

This means that for five years, the task force held the D rating, and for five years, men weren’t receiving regular PSA screening. It’s no surprise, then, that the rate of cancer diagnosis and cancer treatment dropped. Without PSA tests, less cancer was being detected.

Because this type of cancer can be slow-moving, men who had the beginnings of prostate cancer back in 2012, when PSA testing largely halted, may not know it, and may only find out once it’s grown considerably or metastasized. In 10 years, Roehrborn says, it’s possible that we’ll be back where we started: seeing a lot of diagnoses of advanced-stage prostate cancer — the kind that PSA testing, if it hadn’t been demoted to a D by the task force, might have uncovered much sooner.

“There’s no precedence for this,” Roehrborn says. “There’s no cancer where, in the span of 25 years, we went from this totally euphoric state of curing everything to crashing down.”

In the meantime, there have been strides toward a middle ground — for example, the rate of increase in PSA levels between testings and size of prostate compared with PSA levels are now taken strongly into account when deciding whether to biopsy. And technology has also played a key role in helping doctors piece together who has cancer and what their risks are.

2017

/ 60 Years of Prostate Cancer Discovery /

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reverses its D rating of PSA testing to a C for patients ages 55 to 69, recommending that doctors at least discuss the test with their patients.

As it became more common to use ultrasounds to detect cancer, doctors decided to use computer modeling to compare patients’ ultrasound pictures to those of patients already established to have cancer. There was mild success, Roehrborn says, but the models couldn’t quite differentiate with enough clarity. Radiologists had the next breakthrough. Why not, they suggested, use a high-resolution MRI to look for prostate cancer?

It worked. Thousands of images helped doctors gain a better sense of who actually had cancer and who, for example, just had a large prostate and/or high PSA levels. Compared to the invasive procedure of a biopsy, the process of getting an MRI is a breeze — no radiation, no damage to the tissues, no needles.

“The benefit is that the MRI will eliminate about 30 percent of biopsies,” Roehrborn says. “One year we did a million biopsies in the United States. So think about a million MRIs — 300,000 men will walk home free, no biopsy.”

Of course, some of the men who have MRIs will have cancer, but some of them will be small or harmless cancers. And the yield of finding the aggressive, bigger cancers will be that much greater.

Strides forward are also being made in personalized medicine. There are five tests at present that work to match gene expression patterns against a database of thousands of other people. This allows doctors to see how other patients with similar gene expressions were diagnosed, what their PSA levels were, how old they were, and what their lives were like years following the diagnosis, among other details. If the patient matches a large enough percentage of other patients whose cancer was aggressive several years out, doctors will have a good idea of how to treat him. If a patient matches with several others whose cancers stayed fairly benign, doctors will know to monitor him steadily, but that drastic action isn’t necessary.

“It’s an incredible evolution,” Roehrborn says.

The Future

/ 60 Years of Prostate Cancer Discovery /

Radiologists and urologists at large academic centers like UT Southwestern are now working together to overlay MRI and ultrasound imaging of the prostate, providing a more specific and more complete view of a patient’s potential prostate problems, insight into what requires a biopsy, and steps toward faster treatment and fewer fatalities.

With an integrated team of oncologists and radiologists who work cross-functionally to overlay the MRI and ultrasound imaging, UT Southwestern is uniquely positioned to usher in this new era of prostate cancer vigilance. The field has certainly come a long way since that dreaded finger test. For his part, Roehrborn has seen a lot of change since the days when his methodical mentor influenced him to embark on a career in urology. But the systematic, evenhanded way of approaching prostate problems still plays a huge role in his success as a urologist.

“Patients come to me with a PSA problem, a prostate problem,” he says. “I sort of see it as a puzzle and I try to solve their prostate puzzle.”

For Roehrborn, it’s always been about the intellectual challenge. And now, with so much progress made in such a short span of time, there’s only room to grow.