While blood clots are often linked with pregnancy, cancer treatments, and advanced age, some sports injuries can also elevate the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) among younger adults. Most DVT clots occur in the deep veins of the legs, but athletes who perform repeated overhead motions – think basketball players, swimmers, and pitchers – can develop them in their shoulders and arms, too.

Fresh off his All-Star Game debut, San Antonio Spurs center Victor Wembanyama is among several young athletes who have developed a serious blood clot. The team announced that the 21-year-old Rookie of the Year was diagnosed in February 2025 with DVT in his right shoulder and will miss the remainder of the 2024-25 season.

While details of the 7-foot, 3-inch-tall French phenom’s condition have not been reported, the culprit could be thoracic outlet syndrome, in which scar tissue and muscle growth compress the subclavian vein. Left untreated, a blood clot can disrupt blood flow and lead to long-term complications, pain, chronic swelling, and pulmonary embolism, in which the clot travels to the lung.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that about 900,000 people in the U.S. each year develop a blood clot – a mass of blood, cells, and gel-like clotting factors. Most occur in the legs, and only about 5%-10% of clots occur in the arms.

NBA Hall of Famer Chris Bosh, who led his Lincoln High School team in Dallas to a state title in 2002, cut his professional career short after 13 seasons due to blood clot issues. Tennis superstar Serena Williams, who had a history of pulmonary embolism, developed blood clots in her legs after giving birth in 2018. And Sarah Franklin, the 2023 Big Ten player of the year in volleyball, was diagnosed with blood clots in her right arm in 2023.

While upper extremity clots are uncommon, spotting the symptoms and getting medical care fast are critical. March is Blood Clot Awareness Month and Deep-Vein Thrombosis Awareness Month in honor of NBC broadcasting correspondent David Bloom who died of a pulmonary embolism in 2003 while covering the war in Iraq.

Today is the perfect time to learn who is at risk, which symptoms to watch for, and what to expect with treatment and recovery.

Deep venous arterialization kept Irma dancing

For a long and painful year, Irma Villarreal hobbled around on the heel of her foot. It was the only way she could get around. Poor circulation and peripheral artery disease (PAD) had created a condition referred to as “desert foot,” which can occur when cholesterol buildup blocks arteries in the lower extremities and dries up blood flow. The result is intense pain, chronic wounds, and tissue death. Then she learned about a new and little-known procedure called deep venous arterialization (DVA).

Risk factors and symptoms

Anyone can develop an upper extremity blood clot. Athletes who make repetitive overhead arm motions, like dunking or shooting a basketball, are at increased risk of developing thoracic outlet syndrome. This can compress nerves and blood vessels in the upper extremities, leading to scar tissue and a hospitable environment for blood clots.

Professional athletes can have additional risk factors for DVT, including dehydration, taller-than-average height, and long periods of sitting while traveling between games. Other risk factors for DVT include:

- Injury to a vein, most often caused by a broken bone, muscle injury, or surgery

- Increased estrogen from certain contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy after menopause, or pregnancy

- Other medical conditions, such as cancer, heart disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or lung disease, obesity, or a catheter in a central vein

- Personal or family history of DVT or a genetic clotting disorder

In some cases, the first sign of a blood clot may be a medical emergency such as breathing complications or heart failure from pulmonary embolism. Early symptoms of a blood clot can include:

- A cordlike formation in the leg or arm

- Discolored skin that is red, blue, or pale

- Dull ache, tightness, tenderness, or pain in the limb

- Fast heartbeat

- Heaviness, numbness, or discomfort in the limb

- Mild fever

- Skin that is warm to the touch

- Swelling of the arm or leg

If you notice these symptoms, don’t try to wait it out. See a doctor right away, especially if you experience chest pain or shortness of breath – these are signs that the clot may have moved to the lungs. Delaying care can result in serious complications, including limb amputation or death. About 60,000 to 100,000 people in the U.S. die from DVT each year.

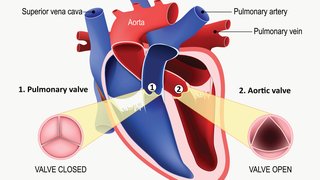

DVT-related blood clots are diagnosed with an ultrasound. If there is concern that the clot is complicated or nearing the heart, an MRI or CT scan can provide more detailed imaging of the clot and the blood vessels.

Treatment for deep vein thrombosis

Most people do not need surgery for DVT, and effective treatments are available that, in some cases, can help athletes safely return to their sport.

Treatment usually includes anti-coagulant medication (blood thinners) to help prevent new clots, stop existing clots from growing, and keep them from breaking free and traveling to the lungs.

In rare cases when a large blood clot blocks a central vein, a patient may need surgery. UT Southwestern interventionalists and vascular surgeons perform minimally invasive surgery to break up and dissolve the clot to restore blood flow. In some cases, the team places a stent in the blood vessel to contain clots and prevent further blockages. After removing the clot, a second surgery may be needed to decompress the blood vessels so blood can flow through freely.

UT Southwestern specialists are leaders in research for developing innovative treatments for blood clots and vascular conditions. Michael Siah, M.D., and colleagues studied the RevCore device, which can help to successfully remove blockages that can form around stents in the blood vessels. Their work suggests RevCore could be an effective new way to treat chronic venous stent occlusion.

Returning to sports

The length of treatment with blood thinners is unique to each person, but the minimum time for treatment with medication is three months. While on blood thinners, patients are at an increased risk of bleeding.

It is not safe for an athlete who is taking blood thinners to participate in contact sports such as basketball, football, hockey, or gymnastics. If they were to fall or take a hit, the result could be bleeding in the brain that can lead to life-threatening stroke, seizures, or a coma.

After a blood clot, young athletes, weekend warriors, and pros alike should discuss activity limitations with their doctor. Resuming sports is possible for some athletes – several NBA players have been in Victor Wembanyama’s shoes and have returned to the court, including:

- Cleveland Cavaliers center Anderson Varejao in 2013

- Toronto Raptors forward Brandon Ingram when he played for the Los Angeles Lakers in 2019

- Los Angeles Lakers center Christian Koloko in 2023

- Detroit Pistons guard/forward Ausar Thompson in 2024

Don’t delay care if you notice signs of a blood clot. Getting help right away can help you get back on the court fast and, more importantly, it can save your life.

To talk with an expert about treatment for blood clots, make an appointment by calling 214-645-0538 or request an appointment online.