It was the day after Christmas and Randy Gideon was waking up from his bi-lateral lung transplant. Laid up and heavily sedated in the ICU, the well-known Fort Worth architect was surrounded by machines with tubes spilling from his torso.

“When I came to, I had this ‘ah-ha’ conscious moment. I could breathe. I still remember how unbelievable it felt to take a deep breath,” Mr. Gideon said.

Just a few feet away, on the other side of the glass window, the transplant team was huddled. Transplant coordinator, pharmacist, social worker, dietitian, physical therapist, nurse, surgeon, and transplant physician were all there discussing Mr. Gideon’s case – just as they do for every transplant patient at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

It takes a robust multidisciplinary team of medical experts to save lives. In all, some 50 people envelope transplant recipients, providing the compass to guide them through their health crisis and to support them long after they leave the hospital.

“As an academic medical center, we bring advanced research to the bedside, benefiting patients who come to our institution with few remaining alternatives,” said Carolyn Swann, Associate Vice President for Heart, Lung, and Vascular, and Solid Organ Transplant Services. “Our multidisciplinary team approach creates a close relationship with patients, providing both cutting-edge and patient-centered care to an increasing number of transplant patients.”

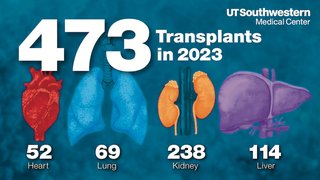

UT Southwestern is nationally recognized and repeatedly honored for its transplant program, which is among the most comprehensive in the nation. With established programs for heart, lung, kidney, and liver, UT Southwestern also is pushing the limits of medicine with the recent approval for hand transplants.

Since UT Southwestern’s first organ transplant in 1988, the entire organ transplant program has made remarkable strides, giving hundreds of patients in end-stage organ failure a second lease on life. For veterans and other amputees, UTSW’s new hand transplant program offers the promise of restoring function and sensation.

But no promise could ever be fulfilled without the dedication of a world-class transplant team.

The Transplant Coordinator

She’s the person who makes the call at 2 a.m. and says, “We have an organ for you!”

Mr. Gideon nearly missed his call. His wife, Beth, had mistakenly turned the phones on vibrate. It was only when he heard the continuous hum of the vibration that he convinced his wife to check her phone. His Christmas gift had arrived late.

A familiar voice was on the other end. Although 20 minutes had passed, there was still time for him to make it, Ms. Alford assured him. The couple would have to pack extra oxygen tanks in their car just to make the drive from Fort Worth to Dallas, but they would get there. His transplant coordinator was there to greet them upon arrival.

Long before a transplant coordinator makes the call announcing an organ has been located, they already have established a special bond with the recipient.

“From the moment we meet, we begin a lifetime relationship,” Ms. Alford said. “We spend long hours and long days with these patients. It’s a labor of love.”

The transplant coordinator is the direct point of contact helping patients survive until they get their organ. “Sadly, people on the waiting list can die, so we want to do every thing we can to keep that from happening,” said Laura Restall, R.N., senior transplant coordinator. The bond strengthens when patients go home.

“We teach them how to live post-transplant,” Ms. Alford said. “Our goal is to help patients restore as much health and vitality as possible.”

But those lives can change in ways that leave a lasting impression on the transplant team.

“Before his transplant, there was one young man who could barely walk across the room without needing oxygen,” said Marcie Buford, senior lung transplant coordinator. “Then one day I saw him running down the hallway. That’s when you know you’re making a difference.”

The Pharmacists

Transplant patients fight organ rejection right from the start. Helping prevent infection and resist rejection is a balancing act that falls to the pharmacists who walk a tight rope as patients deal with an onslaught of medications. It takes a medicine cabinet full of drugs to keep a person thriving following a transplant.

“The first cup they take has 12 to 15 pills in it,” said Dr. Sarah Wright, transplant pharmacist.

Mr. Gideon spends 30 minutes each week organizing his pills into daily doses. Patients meet with the pharmacists prior to hospital discharge to learn what the pills look like, their purpose, dosage, and when to take them.

“Teaching patients about their new meds is one of my favorite things about my job,” Dr. Wright said. “You see the panic on their face when they’re confronted with all these pills, but I’m able to help them become well educated and comfortable with their new medications.”

It can get complex quickly. Pharmacists must be aware of how all the medications interact, including over-the-counter and prescription drugs that patients also may be taking. If a drug is not covered by insurance, Dr. Wright will work in conjunction with the physicians, coordinators, and social workers to search for a less-expensive, but equally effective alternative.

Pharmacists helped Mr. Gideon fine tune the dosage of the anti-rejection medication Cyclosporine, which came in liquid form and must be taken at specific times during the day. Taking the liquid form limited his ability to go out in public, but when he was switched to capsules, his post-transplant life got easier.

“I was still going out with a backpack full of medicine, but I could go out and watch my son play baseball,” Mr. Gideon said.

The Social Worker

From conducting psychological assessments to helping family members file medical-leave paperwork, social workers are at the forefront of patient advocacy. Need a place to stay close to the hospital? Ask a social worker. Need help with exorbitant medication costs? A social worker can help with that, too.

“We are a bridge over troubled waters,” said Martha Jarmon, clinical social worker. And when the waters are the roughest, “we pull out our bag of tricks.”

“Pick the day, we work miracles,” said April Morgan, transplant social worker.

“Surgeons and physicians carry the weight of the responsibility on the team,” Mrs. Morgan said. “But to a family with no place to stay, no food to eat, and a general lack of concrete resources, the care social workers provide means just as much.”

The Dietitian

What is the one food transplant patients can’t eat?

Grapefruit. It interferes with the essential anti-rejection medication.

And to a transplant patient, a baked potato is a healthy food choice. “It has half the potassium a kidney patient needs for the day,” said Lynn Henderson, registered dietitian.

Without a dietician teaching patients how to eat after a transplant, organ recipients can easily make some dangerous choices.

Long before a transplant occurs, dieticians are busy individualizing a nutrition plan and helping recipients learn to make healthy choices. When someone needs to lose or gain weight, dieticians are there to help.

If a person’s body mass index (BMI) is too high, a nutritionist can work with them to lower it to an acceptable level in order to get on the organ list.

“A lot of fat in the mid-section makes surgery more difficult,” said Francis Dang, registered dietitian.

For a lung transplant, acceptable means a BMI less than 30. For a heart and kidney, it is less than 35. But for liver, it goes up to 40. A normal BMI is between 18.5 and 24.9.

Post-transplant patients need to take dietary precautions to counterbalance the side effects of their medications. Increased blood pressure, high cholesterol, and weight gain are among the issues addressed by nutritionists.

“We help patients make better dietary decisions,” Ms. Dang said.

For Mr. Gideon, pulmonary fibrosis had ravaged his lungs, leaving him inactive and 40 pounds underweight. Dietitians counseled him on weight gain measures he could take at home, in conjunction with his exercise regime prescribed by physical therapists.

The Physical Therapist

“When I left the hospital, I was so weak that stepping up a curb was almost unimaginable,” Mr. Gideon said.

Like many lung transplant recipients, Ms. Gideon had lost every shred of strength and stamina. Not surprisingly, lung transplant patients often are apprehensive when they start pulmonary rehabilitation.

Sometimes they come in using a wheelchair, said Rebecca Parnell, a physical therapist who works with lung transplant recipients.

“They have that scared deer-in-the-headlights look,” she said, “But when they leave they are already walking a mile.”

Mrs. Parnell is firm but gentle as she teaches patients exercises to restore their range of motion, to increase their strength, and to improve their balance. Their bodies are not used to any of it after months of bed rest.

“The beautiful thing about the body is that it adapts to stress,” Mrs. Parnell said. “My job is to stress them at a safe level.”

Patients face a lot of peaks and valleys during their journey toward recovery, but if they don’t give up, they will be able to accomplish their goals.

“I had one patient who I don’t think believed she would ever walk again,” Mrs. Parnell said. “But she did it, little by little, she got stronger.”

Mr. Gideon hopes that with time and hard work, he too will regain his stamina.

“I was really into fly fishing, and I hope to do it again,” he said. “I’ve just got to get my stamina back and feel like I have the strength to stand in a river or ocean.”

During their transplant journey, patients are put at the center of the transplant team, members of which work tirelessly to help ease the burden of undergoing a life-changing surgery.

Along the way, financial coordinators help them wade through the mountains of insurance-related paper work. And speech pathologists assist lung transplant patients with re-learning to swallow after surgery.

For lung transplants, UT Southwestern ranks among the highest in one-year and three-year survival rates after transplantation. UTSW, which began its lung transplantation program in 1990, has an 84 percent survival rate one year after surgery and a 70 percent survival rate three years after surgery.

“Transplant changes you physically and emotionally and in lots of ways you don’t realize until you’re in to it,” Mr. Gideon said.