A recent study published in The Lancet has cast shadows of doubt on the effectiveness of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), also known as angioplasty or stenting. The Objective Randomised Blinded Investigation With Optimal Medical Therapy of Angioplasty in Stable Angina (ORBITA) study found no significant benefit to stenting over placebo in a small pool of people with stable angina, or chest pain. Unfortunately, a follow-up article in The New York Times has sparked a misperception that the ORBITA data are definitive and substantial.

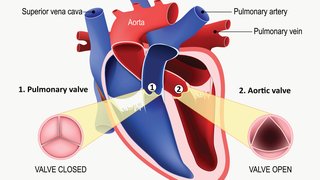

PCI is a procedure in which a small tube called a catheter is inserted into a blood vessel in the wrist or groin and directed to the blocked artery. Through the catheter, a tiny device called a stent is placed in the blocked artery to help keep it open and improve blood flow. PCI has been well-documented as a lifesaving therapy for patients who are suffering heart attacks and also as a pain-reducing treatment for individuals with multiple blocked arteries who suffer angina.

It’s critical to note that people suffering heart attacks and those with multiple blocked arteries were not in the patient demographic studied in the ORBITA trial. ORBITA participants were:

- Diagnosed with just one blocked artery: Individuals with more than one blocked artery were excluded from participation in the trial.

- Diagnosed with stable angina: This is chest pain that is being treated with oral medications on an outpatient basis.

- Analyzed just six weeks after stent placement: That timeframe may not be long enough to be statistically significant.

- Part of a small pool: The study included just 200 participants.

Comparing the patients in the ORBITA trial to severely ill, hospitalized patients with multiple blocked arteries is like comparing apples to green beans. While some aspects of the ORBITA study were well done and interesting, the data are not definitive enough to change treatment recommendations for angina patients across the board.

Basics of the ORBITA study

ORBITA was a blinded placebo study, meaning the participants were not told whether they received a stent or a placebo, which is a harmless therapy that doesn’t have a medical effect. In this study, the placebo was a catheter procedure without a stent placement. The primary measurement of the study was whether participants who received stents could improve their ability to exercise on a treadmill more than participants who received the placebo procedure.

In the study, individuals who received stents increased their baseline treadmill time by about 28 seconds, compared to those in the placebo group who improved by about 12 seconds. While both groups experienced improved endurance, neither increase was drastic enough to be considered statistically significant for or against stenting as the preferred treatment for stable angina.

What would it take to make the ORBITA data significant?

Larger, more diverse participant demographics

ORBITA was small – too small, in fact, considered definitive evidence that cardiologists should change the role of stents in clinical practice.

I participate in a number of cardiology care guidelines committees and even wrote a piece about the ORBITA trial for the American College of Cardiology. In order for regulating bodies to change clinical practices, research studies must present data from a much larger pool, such as the 2007 COURAGE PCI study, which enlisted more than 2,000 participants. In general, larger trials present data that are more statistically significant and more appropriate to apply to specific patient segments.

Additional research sites

When a study occurs at one hospital or within one system, the level at which the hospital environment or culture biases the data increases. Conducting the study at additional sites in different parts of the country or world will establish credibility to the data and reduce demographical concerns, such as geographic or ethnic risk factors.

A longer timeline

The ORBITA study may be too short of a follow-up period to gauge significant changes in physical or quality-of-life metrics. Participants were given an initial exercise test on a treadmill and a questionnaire about their quality of life. They then received either a stent procedure or a placebo catheter procedure in which no stent was placed, as well as six weeks of intensive medical therapy. After six weeks, participants were reassessed for treadmill stamina and quality of life.

Ideally, the trial should be conducted over a longer time frame (several months) to gauge real changes in quality of life and long-term health that might move the needle on how we recommend stenting versus other therapies.

An interesting factor in this study

The ORBITA study introduced one important element that we should consider implementing for future research on PCI: When a person receives a medical procedure, whether it is clinical or a placebo, the individual can experience a placebo effect. In other words, if a person thinks care was given, symptoms might improve regardless of whether the care was real or perceived.

This is a concern with many studies, and ORBITA took this into account by giving a procedure to every patient, rather than comparing medicine-plus-stenting therapies to medicine alone as many studies have done before. The ORBITA researchers even went so far as to put noise-canceling headphones on the participants so they wouldn’t know whether they’d received a stent or the placebo procedure.

How we prescribe stents in our practice

At UT Southwestern, we typically use medications before suggesting stenting. That said, if I see a serious blockage, even if it is in just one of the arteries, I typically recommend fixing it if there is evidence that it is causing symptoms by limiting blood supply to the heart. Though all procedures carry some risk, the risk of stenting is incredibly low at less than 1 percent.

Ultimately, we don’t want misperceptions about the ORBITA study data to wash away decades of effort among cardiologists to provide lifesaving stent therapy to patients with unstable angina and heart attacks. The way we talk about and approach research around stenting could cause substantial negative ramifications in patient outcomes if we aren’t crystal clear about who can benefit from PCI and who likely won’t.

We look forward to continued research into the effectiveness of stenting for symptom management in stable angina patients. Until then, we’ll stay the course on our recommendations for the least invasive and most effective therapy for each individual. At the end of the day, your treatment should be selected after thoroughly exploring your options with your doctor.