What you should know about Chagas disease in North Texas

December 12, 2025

If you’ve ever donated blood, you may recall being asked one or both of these questions on screening forms:

“Do you have or have you ever had Chagas disease?”

“Have you traveled to or lived in a country where Chagas disease is common?”

If you are like most people in the United States, you probably aren’t entirely sure what Chagas disease is. In fact, routine screening of the U.S. blood supply for Chagas disease only began in 2007.

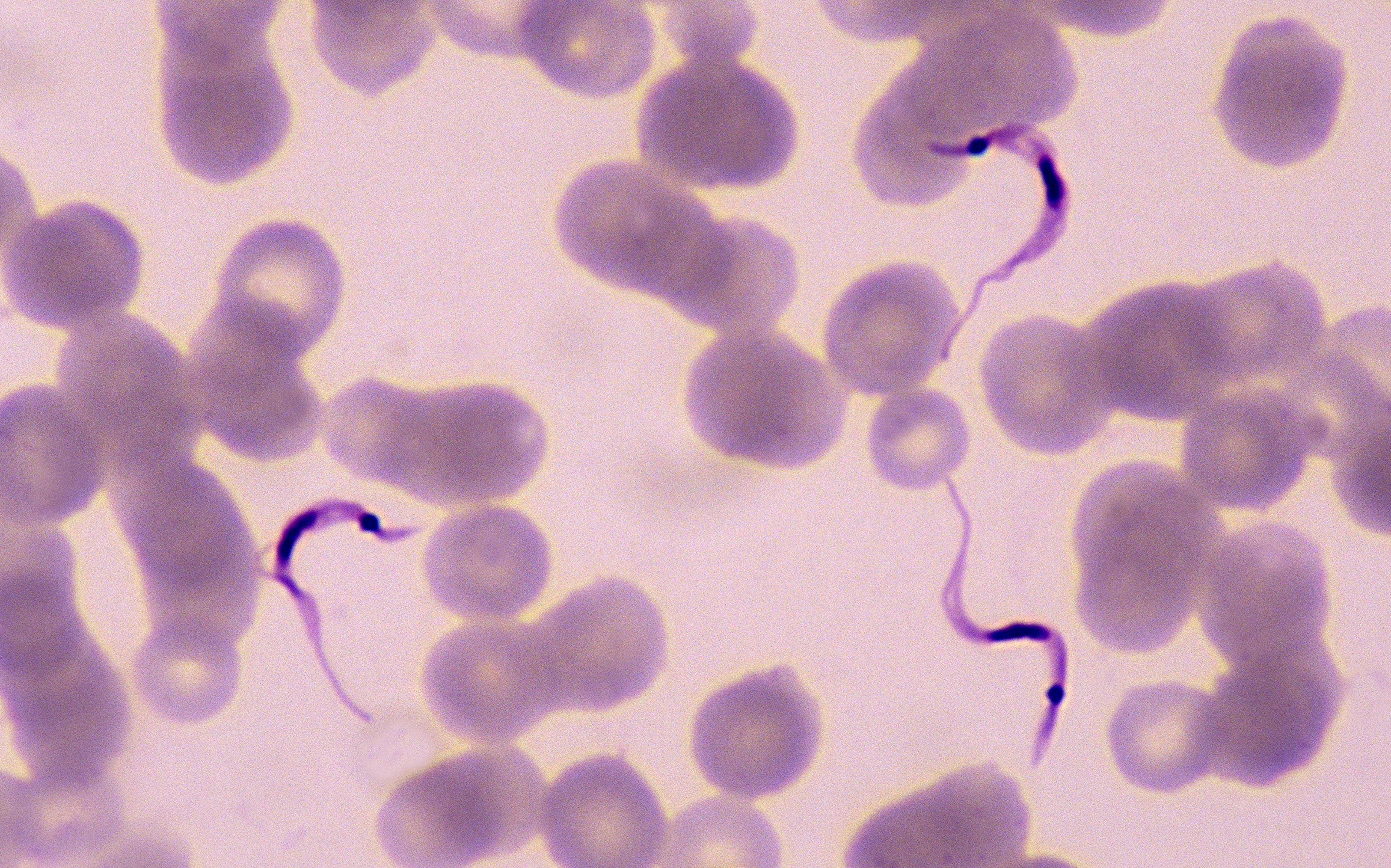

Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis, is an infection caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. The disease is most commonly transmitted when a triatomine “kissing bug” bites a person and then defecates near the bite, allowing the parasite in the bug’s feces to enter the body through the bite wound, broken skin, or the eyes or mouth.

The disease is not transmitted from person to person but can spread from mother to baby during pregnancy, and less commonly through contaminated food or drink, blood transfusions, or organ transplantation.

Globally, an estimated 6 million to 8 million people – most of them in Latin America – are infected with Chagas disease, including an estimated 280,000 in the U.S., many of whom are unaware they carry the infection. Untreated, the disease can progress and become life-threatening.

In its chronic phase, Chagas can lead to serious complications of the heart, esophagus, and colon. It is one of the leading causes of heart disease in Latin America and, according to global studies, causes more disability than other vector-borne infections, including Zika and malaria.

Kissing bugs have been found across many parts of the southern U.S., including Texas. While Chagas disease remains most common in Central and South America, autochthonous (locally acquired) infections have been reported in eight U.S. states – “most notably in Texas,” according to a recent report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Between 2013 and 2023, the Texas Department of State Health Services documented 50 probable or confirmed locally acquired cases, meaning individuals were infected within the state rather than while traveling to endemic countries. These cases were identified either through known exposures to infected insects or in people without a history of travel to a disease-endemic region.

At this time, the risk to residents in the Dallas-Fort Worth area remains minimal. However, awareness is crucial.

Common treatments

Two antiparasitic medications, benznidazole and nifurtimox, are the main treatments for Chagas disease. These therapies are most effective when given soon after infection but can still provide benefit in certain patients with chronic infection, especially younger individuals.

For those who develop chronic complications, management may include heart failure medications, pacemakers for cardiac disease, and surgical treatment for digestive tract problems.

Chagas disease symptoms

Symptoms of Chagas disease vary by stage.

In the acute stage, symptoms are often absent or mild and may go unnoticed. Common symptoms include fever, swelling at the bite site, fatigue, rash, headache, loss of appetite, diarrhea, vomiting, or body aches. Some individuals develop painless swelling of the eyelid known as Romaña’s sign.

In approximately 30% of patients, Chagas disease progresses to a chronic phase that can emerge years or even decades after infection and result in serious complications including:

- Heart rhythm abnormalities

- Dilated cardiomyopathy or heart failure

- Difficulty swallowing due to esophageal disease

- Severe constipation or bowel enlargement

What's in the CDC report?

The World Health Organization classifies Chagas disease as a neglected tropical disease. The Pan American Health Organization considers it endemic, or regularly occurring, in 21 countries in the Americas, excluding the U.S.

However, the CDC’s recent report argues that growing evidence supports classifying Chagas disease as endemic in the U.S. Triatomine insects have been identified in 32 states, and nine of the 11 U.S. species are known to be naturally infected with T. cruzi. Four species, including Triatoma gerstaeckeri, are commonly found near homes, raising the possibility of local transmission.

Wild animals, such as opossums, raccoons, armadillos, skunks, woodrats, and coyotes, as well as domestic animals – especially dogs – can harbor the parasite, serving as reservoirs for infection.

Locally acquired human infections of Chagas disease have been confirmed or suspected in at least eight states: Texas, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee. Only eight states require mandatory reporting of the disease: Arizona, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and Washington, as well as two California counties. Although a new surveillance case definition was implemented in 2024, experts remain concerned that Chagas disease is significantly underdiagnosed and underreported.

The CDC report warns that labeling the disease as “nonendemic” in the U.S. contributes to low awareness and underinvestment in surveillance, research, and public health responses. While the report primarily highlights disease ecology and surveillance, it also underscores the importance of recognizing local transmission.

Should North Texans be concerned?

Most locally acquired Chagas disease infections in Texas have been linked to rural or outdoor exposure rather than urban settings. While the overall risk in North Texas remains very low, those in rural areas may face heightened risk. Greater awareness among residents and health care providers can help ensure timely diagnosis and access to treatment.

According to a recent report in The Lancet, non-endemic regions such as the U.S. have experienced notable increases in Chagas disease cases due to migration from countries where the disease is endemic. Since Texas’ population includes a substantial number of immigrants from endemic countries, it is vital that we maintain mindfulness about the disease as well as access to screening and care.

If North Texans develop Chagas-like symptoms after outdoor/rural exposure, they should consult a physician to be evaluated. The disease can be diagnosed with blood tests, and getting early treatment is key.

To talk with an expert about Chagas disease, make an appointment by calling 214-645-6427 or request an appointment online.