While it may not be a household name, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is the most common genetic heart condition, affecting 1 in 500 people. Many of these people will never experience symptoms or even know they have it. But for a few, the disease can cause significant problems, including shortness of breath, chest pain, abnormal heart rhythms, cardiac arrest, or heart failure.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is characterized by abnormal thickening of the heart muscle, making it difficult for the heart to pump blood and rendering patients susceptible for arrhythmias (abnormal beating of the heart). Treatment options for symptomatic patients range from medication to surgery, and can depend on specific features of the condition. Even some patients without symptoms are at risk for cardiac arrest. Care for these patients is complicated – and patients and referring physicians often seek a doctor who specializes in the condition.

This was the case for Dallas resident Lisa Hopkins, whom I first treated in 2003 when I was at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. Thirteen years later, we reunited when I came to practice at UT Southwestern. We have the only comprehensive HCM program in North Texas, which includes Dr. Bajona, Dr. Turer, Dr. Grodin, and me, as well as partners at Children's Healthin Dallas.

Lisa is an excellent example of a patient who advocated for herself and her care, learning all she could about her condition and making sure she was seeing the right doctors to treat it – no matter how far she had to travel.

Here is Lisa’s story in her own words.

***

A startling diagnosis

It all started in January 1993, when I was 32. After experiencing a series of heart palpitations, I finally went to my primary care doctor. He did an electrocardiogram (also known as an ECG or EKG) and said, “That’s not normal. You need to see a specialist.” A cardiologist performed an echocardiogram and diagnosed hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

I was terrified at first. I kept thinking about Hank Gathers, who a few years earlier had collapsed during a basketball game for Loyola Marymount University and died of HCM. I thought my heart would just stop, which for many people is the first indicator that they have the condition.

I was prescribed beta blockers (medication to control abnormal heart rhythms), which controlled my symptoms for nearly 10 years. But then in 2001, I had an abnormal heart rhythm episode. By 2003, it seemed like I was going to the emergency room every week.

It was then that I contacted Lisa Salberg, the founder of the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Association (HCMA). Most general cardiologists see few patients with HCM in their daily practice. The HCMA keeps track of hospitals and practices that do see a high volume of HCM patients, but at the time, the site didn’t have any locations listed in Texas.

When Ms. Salberg mentioned Tufts Medical Center in Boston, I thought, “Well, my best friend from college lives there, so at least I’ll know someone.” I scheduled an appointment with three doctors, one of whom was Dr. Link.

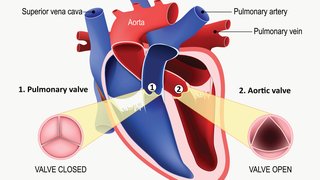

The team changed my medication and recommended an atrial fibrillation ablation. In this procedure, the doctor inserts a catheter through a vein in the groin and up into the heart. Atrial tissue growing into the pulmonary veins is cauterized, which can prevent an irregular heartbeat known as atrial fibrillation.

The procedure worked, and I was symptom-free for a little more than a year. Life was good. But unfortunately, the arrhythmias started again in 2005.

A decade of procedures, then a reunion

In 2005 in Dallas, I had a maze procedure, which is a surgical ablation that treats atrial fibrillation, or irregular heartbeat. This procedure worked for about nine months, at which point the symptoms returned and I had to change medications again.

The next year, I was referred to Dr. Warren Jackman at OU Medicine in Oklahoma City for yet another ablation procedure.

While in the hospital recovering from the ablation, I went into cardiac arrest. I was lucky I was still in the hospital because had it happened at home, I likely would not have survived. I was taken straight back into surgery for placement of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). This device monitors my heartbeat and delivers an electrical shock if it detects an abnormal heartbeat. I call it “Thumper.” ICDs last about five years, so I went from “Thumper 1” to “Thumper 2” in 2011.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy causes the heart muscle to be stiffer than normal heart muscle, causing it to squeeze too hard. One of the medications that helps it relax some also causes the mitral valve to take a beating. I had open heart surgery to replace my mitral valve in 2008.

In November 2016, after noticing changes in the way I felt over the past year and a half, I began looking for a new doctor who better understood hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

I was considering traveling for treatment when I saw a Facebook Live video in which Lisa Salberg with HCMA mentioned Dr. Link and UT Southwestern in the same sentence. I immediately looked it up and there he was, right here in Dallas! I canceled my appointment with my cardiologist and made one with Dr. Link.

I walked in to the appointment a week later and said, “Hey, I saw you 13 years ago in Boston, and here I am, and here you are.” He determined that “Thumper 2” was at the end of its life, so I got “Thumper 3.” Two weeks later, I was standing in line at the grocery store when I began to feel poorly. The device did its job and shocked me, and I ended up in the hospital for a couple days.

At that point, Dr. Justin Grodin also joined my care team as a heart failure and transplantation specialist. We’re in the middle of lots of testing to determine next steps, but I feel fortunate to have a team right here in my hometown that truly understands my heart problem.

Being my own best advocate

I’ve been lucky to have good medical teams over the years. But I also put in a lot of work advocating for myself. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve gone to the emergency room and, after telling them a certain drug never works on me, they want to try it anyway. Doctors and nurses are well-educated, but nobody knows your body like you do.

An HCM diagnosis may seem overwhelming, but you can advocate for yourself and ensure you’re getting the best possible care:Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a struggle. Shortness of breath and a racing heart are difficult to deal with physically, but it also can be mentally taxing to constantly worry about symptoms or wonder when they’ll strike again. I have a three-day rule: I can cry or complain for three days, but then I have to just get on with life.

You only have so many days, so many heartbeats. You can choose to live in fear and denial, or you can choose to live every day to its maximum. I can’t leave HCM behind, but I can choose to put my energy into living the best life possible. I can put it in God’s hands and say, “OK, you’re in control of what happens next.” Twenty-four years later, I’m still here. My story continues.

- Don’t ignore symptoms. See your doctor.

- Get a second opinion. Find a specialist who sees a high volume of patients with HCM.

- Educate yourself. Read everything you can and learn as much as possible. Don’t worry, you’ll pick up the language and things will start to make better sense.

- Take a family member or friend to appointments. Ask this person to listen and take notes for you. Sometimes it becomes overwhelming. Your brain will just stop and you won’t hear what’s being said. This way, you won’t miss anything.

- Speak up and ask questions. You don’t know what you don’t know, and your doctor will understand that.