New mom survives SCAD heart attack, hole in her heart, 4 a.m. surgery

March 10, 2022

Kelly Stebbins had enjoyed good health her entire life – she’s never broken a bone or even had a cavity, she said. Her first pregnancy and the delivery of her daughter, Emery, was easy and “uneventful.”

So, when Kelly began experiencing symptoms of a heart attack at work a few weeks after returning from maternity leave, she couldn’t quite believe what was happening as she called 911. Her situation turned so dire that paramedics had to restart her heart twice in the ambulance on the way to another hospital in the Metroplex.

Doctors there confirmed Kelly had a heart attack, but they couldn’t pinpoint the exact cause. Kelly’s sister, a doctor, recommended she be transferred to UT Southwestern.

That request – and an overnight emergency surgery – saved Kelly’s life.

At UT Southwestern, we discovered Kelly had what’s called a pregnancy-related spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) – a type of heart attack caused by a tear within the layers of the artery walls that cuts off blood supply to the heart. SCAD is rare and can be extremely serious.

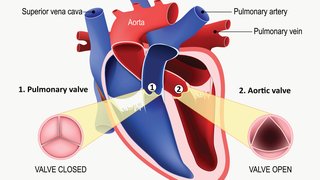

Ultimately, the heart attack caused a large hole between the right and left sides of her heart and set in motion a very tense night in the operating room. In fact, we arranged a video call with her family and newborn in case the damage was too extensive to repair.

Michael Wait, M.D., Chief of the Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery Service at William P. Clements Jr. University Hospital, who led our surgical team, describes the procedure to patch the hole in Kelly’s heart as “one of the highest-risk operations we as heart surgeons ever perform.”

Throughout her ordeal, Kelly displayed an unyielding will to survive for her infant daughter. A year later, she is doing amazingly well and keeping up with Emery, who is now an active toddler.

Kelly’s case is a cautionary tale. If she and her sister had not trusted their intuition and decided to go home – or even waited a few more hours – she might not be here to share her story.

‘Someone my age doesn’t have a heart attack for no reason’

By Kelly Stebbins

I gave birth to my daughter, Emery, on Jan. 22, 2021. Everything was going well at home, and I had returned to work as director of an At Home store, ready to be back in action.

But on April 6, when my heart started racing, and I began sweating profusely, I knew something was wrong. I called 911 and said I thought I was having a heart attack. I even laid down on the floor because I thought I might pass out and hit my head.

When the paramedics arrived, I was alert, but soon everything went dark. I woke up in a community hospital, where I stayed for three days. The doctors there did several tests but couldn’t find what caused the heart attack, which was concerning and somewhat frustrating. They wanted to put me on a thyroid medication and place an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) in my chest – a battery-powered device that can detect abnormal heart beats and restore a normal rhythm.

My sister, the doctor, knew something wasn’t right – someone my age (41 at the time) and in good health doesn’t just have a heart attack for no reason. She called UT Southwestern, and I was transferred by ambulance a little after midnight.

Once I arrived, the heart team repeated a few of the other hospital’s tests. Because they are heart specialists, they quickly diagnosed me with SCAD. I was relieved to finally have an answer and so grateful that I’d been transferred.

After I got settled in my room, I asked one of the nurses to help me get in the shower. Within moments, my heart started racing again, just like it had at work. The last thing I remember was the nurse shouting for the doctors to come right away.

‘They found a dime-sized hole in my heart’

Listening to the heart team retell the tale weeks later, it sounded like an episode of ER. Dr. Hall and Dr. Wait told me they had ordered a heart ultrasound (echocardiogram) and a heart catheterization to confirm the diagnosis. They also placed an intra-aortic balloon pump during the catheterization to help stabilize my condition.

They found a dime-sized hole in my heart wall.

Unfortunately, this only bought us a little time, and I was rushed to surgery early the next morning.

Around 4 a.m., the cardiothoracic surgical team rallied for my emergency open-heart surgery. They placed a patch over the hole in my heart, carefully attaching it to my damaged heart muscle. During the procedure, my blood pressure kept dropping dangerously low; they had to leave my chest open for three days before my blood pressure stabilized enough to withstand closing me up.

Coming out of anesthesia, I’m told I was sort of a bear – yelling, demanding, the whole nine yards! Dr. Hall and I joke now about my feistiness, but I can’t recall anything I said.

I stayed in the ICU for three weeks. My family traveled from Kansas City and Denver to be with me and take care of Emery, and my co-workers were steadfast in my absence, pitching in to support my family.

Of all the challenges I faced that month, the hardest was not being able to be with my baby. I could see her on video calls in my room, which were wonderful, but yet it wasn’t the same. When I was strong enough, a doctor wheeled me to the lobby – one of my family members had brought Emery for a visit! Though I couldn’t hold her yet, I could touch her hair and kiss her cheeks. This is just one example of the kindness my care team showed me as I recovered.

I get emotional now just thinking about it. I was in the best hands at UT Southwestern, and I was incredibly lucky.

Getting stronger…and eating peaches

I started cardiac rehabilitation a few days after surgery. After all the stress on my body, I had to relearn how to do daily activities, even feeding myself.

But I will say, food never tasted so good as those first few bites when I was strong enough to eat. In fact, a nurse sprinted into my room moments after I took my first bite of peaches in weeks – my heart rate had jumped with joy, sounding a heart monitor alarm!

After I left the hospital, I continued with rehab for three months, working my way up to climbing stairs and eventually being strong enough to pick up Emery again.

Since October 2021, I have been able to resume most of my normal activities. I take medication to reduce the workload on my heart, and I get a little winded if I overexert myself. But I’m back at my job again, and now I’m chasing after an active toddler!

Every few months, I visit Dr. Hall and the team to make sure the patch in my heart is still working properly. Everyone I met at UT Southwestern went the extra mile for me, and they celebrate my good health when we reunite at my checkups.

Though SCAD is rare, I hope people will take two things away from my experience. First, pay attention to your body – if something doesn’t feel right, don’t hesitate to ask for help. Second, if you don’t feel comfortable with the care you’re receiving, get a second opinion or seek care elsewhere. I did, and it saved my life.

Know the signs of pregnancy-related SCAD

When Kelly’s condition quickly declined, multiple experts collaborated immediately to help her, including Jennifer Smith, M.S.N., APRN, AGACNP-BC, a cardiac nurse practitioner who was one of the first providers on the scene after Kelly crashed in the shower.

That’s one of the benefits of obtaining your care at an academic medical center like UT Southwestern – we have a diverse staff of specialists who all work in one place, 24/7.

Kelly’s survival and recovery are nothing short of amazing. Meeting her now, you’d never suspect that she survived such a traumatic health challenge.

While rare, SCAD is the most common cause of a heart attack during pregnancy or after a patient gives birth. Research is ongoing, and some studies suggest changes in hormone levels may increase the risk.

Related reading: The ‘fourth trimester’: Why women need health care after delivery

If SCAD is detected early enough, minimally invasive treatment can restore blood flow to the heart and avoid creating a hole in the heart. A damaged artery might also heal on its own but will require close monitoring. In some instances, doctors could place a stent or conduct a bypass procedure to restore blood flow without open heart surgery.

Yet SCAD continues to be misdiagnosed, underdiagnosed, and managed improperly, according to a scientific statement by the American Heart Association.

Kelly’s case highlights the importance of being able to diagnose spontaneous coronary artery dissection and treat it quickly and appropriately. It should also emphasize to patients that when it comes to your heart health, you don’t have to accept the first answer. If something doesn’t feel right, ask for a second opinion, no one will be offended. Another perspective and more specialized skills can make all the difference.

To talk with a doctor about heart health, call 214-645-8000 or request an appointment online.