At age 60, four-time Super Bowl-winning linebacker and former NFL broadcaster Matt Millen faced fatigue, extreme weight loss, and general inability to do the simplest physical tasks. After years of misdiagnoses ranging from severe acid reflux to Lyme disease, doctors discovered that Millen had AL, a variation of the complex disease amyloidosis.

Amyloidosis is characterized by proteins that "misfold." Imagine the proteins as 3-D origami figures with perfectly folded edges. In patients with amyloidosis, the folds are imperfect, and the protein can't hold its structure.

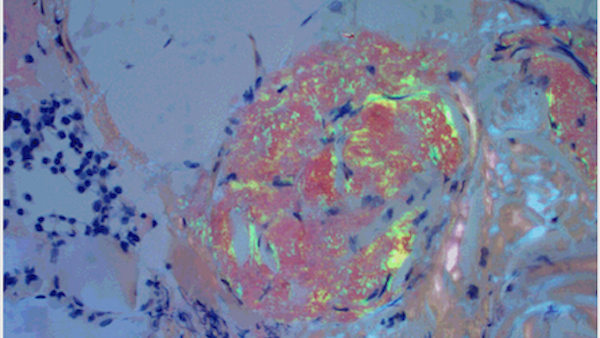

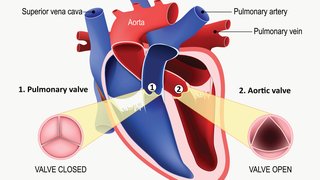

The protein breaks down into a substance called amyloid, which can travel through the body and deposit in the organs like excessive mortar in a brick wall. Most commonly, amyloidosis affects the nervous system and the heart, causing neuropathy, heart failure, or both.

Approximately 95 percent of amyloidosis cases that affect the heart are classified as AL or ATTR cardiac amyloidosis:

- AL is the most common type of amyloidosis and is associated with a bone marrow disorder. AL is aggressive, with a median survival of five to seven months without treatment. Patients with AL, like Millen, typically receive chemotherapy and, uncommonly, may need a heart transplant, which Millen received on Christmas Eve in 2018.

- ATTR can be either hereditary (caused by a mutation in the TTR gene) or wild-type (not associated with a genetic mutation). The median survival is two to five years without treatment. Until recently, there were zero treatments for nerve- or cardiac-involved amyloidosis approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

But in 2018, two therapies, inotersen and patisiran, were approved by the FDA for hereditary nerve-involved ATTR. And in 2019, tafamidis became the first FDA-approved drug for hereditary and wild-type cardiac ATTR. The therapies work differently based on the type of cardiac amyloidosis involved, and UT Southwestern is developing a multidisciplinary amyloidosis program to care for all patients with this condition, which was previously considered untreatable.

In this article, we'll delve into ATTR, the less common of the two main types of amyloidosis.

Who is at risk for hereditary and wild-type ATTR?

Breaking down ATTR a bit further, the most common genetic mutation in the U.S. for hereditary ATTR is prevalent in 2% to 4% of African-Americans and people of Afro-Caribbean descent. This mutation is associated with an increased risk of heart disease.

This is very different from wild-type ATTR, which can be thought of as a deviation from the normal aging process. From autopsy studies, we know that as many as 25 percent of adults will have amyloid deposits in their hearts when they die, assuming they live to be 80 or older. But we don't yet understand why some patients develop heart disease and require treatment while others don't.

"Amyloidosis is characterized by proteins that "misfold." Imagine the proteins as 3-D origami figures with perfectly folded edges. In patients with amyloidosis, the folds are imperfect, and the protein can't hold its structure."

Justin Grodin, M.D.

New cardiac amyloidosis treatments

The recently approved drugs are helping patients and providers shift their thinking about cardiac- and nerve-involved ATTR. It's no longer considered a rare and hopeless disease. Now, we see ATTR as a condition that can be managed, giving patients better outcomes and improving their quality of life.

Cardiac ATTR treatment

Tafamidis has been shown to slow the progression of cardiac-involved ATTR. Going back to our origami visual, tafamidis acts like a bit of glue to hold the protein folds in place, stabilizing TTR proteins so they don't misfold.

While tafamidis doesn't cure or reverse cardiac ATTR, the drug has been shown to reduce the risk of death by 30% and reduce the frequency of cardiac-related hospitalization, according to data published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Nerve ATTR treatment

The drugs approved for nerve-involved ATTR greatly reduce the production of TTR proteins in the liver. Some proteins are still made, and those that get through the liver and into the body do misfold. However, their numbers are greatly reduced, which subsequently reduces symptoms.

Diagnosing ATTR

Diagnosing ATTR requires a healthy amount of suspicion and some detective work because of the vagueness of the symptoms. More than 10% of patients are symptomatic for three years or longer before they are diagnosed with cardiac ATTR.

Amyloidosis can be diagnosed noninvasively with a blood test that will test for AL, another amyloidosis disease, and a routine heart scan (nuclear medicine study). Standard cardiac echo and MRI can also be used. Sometimes a heart biopsy is needed, and we gauge this by whether the other tests yield ambiguous results.

Too often, ATTR is recognized after it has progressed to a point where outcomes are likely to be poor. Today, the median survival of a patient with amyloidosis is two to five years. However, with newer imaging techniques and a better understanding of early markers of the disease, we have the capacity to change the natural history of the disease.

A distinct specialty program is needed to accurately diagnose ATTR, determine the disease type, and align available treatment options. As such, we are developing a cross-department amyloidosis program to better serve our patients and referring physicians across the U.S.

Our vision for a multidisciplinary amyloidosis program

We offer a comprehensive, patient-centered approach to diagnosis and treatment.

Because of the many causes of amyloidosis, patients will need to see a variety of specialists. Key members of our program include:

- Cardiologists with expertise in heart failure and advanced heart imaging

- Neurologists with expertise in neuropathy

- Pathologists

- Specialized nurses

- Clinical pharmacists with a thorough knowledge of the therapies

- Researchers who will continue to optimize and discover therapies

- Other specialists to provide whole-patient care

Patient support is an important element of amyloidosis care. We are involved with amyloid support groups and the Amyloidosis Foundation. We will also be participating in several clinical trials in the next few years to study the effectiveness of other drugs for ATTR.

Because we receive a large number of referrals for amyloidosis, this move to develop an amyloidosis program is a natural fit for our medical center. We will leverage our leadership and expertise across departments and translate cutting-edge research into actionable, personalized care for patients with amyloidosis.

If your cardiologist has voiced concerns about the prospect of amyloidosis, consider visiting our specialized center. Call 214-645-8300 or request an appointment online.