On a cloudy Wednesday in May, I’m standing in a strip mall parking lot trying to take a decent selfie.

The wind is having a field day with my hair, but I can’t really ask for help with the photo because: a) there are very few people around; b) we’re in the middle of a global pandemic; and c) it would take too long to explain why I want to mark this occasion in front of a white bus stretching across four parking spaces.

Beneath my flowery mask and sunglasses, however, I am smiling wide because this appointment at the Carter BloodCare mobile collection station means two very important things:

- I am fully recovered from COVID-19.

- And I am finally able to donate my plasma, rich with virus-fighting antibodies. There’s a reason they call it “liquid gold.”

Two months earlier, the novel coronavirus turned my world – the entire world – upside down. For nearly two weeks, I was alone in my bedroom with excruciating headaches, unrelenting body aches, and inescapable fear. There were moments when I wasn’t sure I’d make it.

But today, as I get ready to participate in UT Southwestern’s trailblazing convalescent plasma program, I am feeling strong and fighting back against COVID-19, energized by the possibility that my plasma might be able to save some lives.

That’s gotta be worth a few selfies, right?

A science geek and a survivor

My name is Claire Aldridge and I am the Associate Vice President of Commercialization and Business Development at UT Southwestern Medical Center. That’s a long way of saying I’m a lifelong science geek who every day gets to collaborate with some of the best minds in the business to advance discoveries, moving them from the lab to the real world.

Our mission is to turn science into medical solutions for patients.

I have a Ph.D. in immunology and genetics from Duke, and while I never had the patience to become a bench scientist, I have an abiding faith in research, the human immune system, and modern medicine. That belief brought me back to Texas in 1996, shortly after I completed my Ph.D. My father had been diagnosed with metastatic melanoma and was given less than two years to live.

Today, Dad is 85 and cancer-free, thanks largely to the power of clinical trials and innovative therapies. So, you see, my experience is both professional and very personal.

I would have to draw upon that bedrock of faith again in early March when my husband, my 12-year-old daughter, and I all became infected with COVID-19.

The day everything went sideways

Way back in January, we bought tickets for a Spring Break trip to New York City. My daughter is a serious musical fan, and we wanted to take her to see the bright lights of Broadway. Our flight was scheduled for March 11, the day everything went sideways.

That morning, we checked the CDC’s website, which said there were only a few confirmed cases of COVID-19 in New York City. Other than one hot spot in the suburb of New Rochelle, there were no significant outbreaks in the Big Apple. So we packed our wipes, gloves, and hand sanitizer and flew out of DFW Airport hoping to embark on a memorable theater weekend.

By the time our plane landed, the world had changed:

- The World Health Organization declared the spread of COVID-19 had reached pandemic proportions.

- The U.S. banned travel from parts of Europe.

- The NBA basketball season was suspended.

- And Oscar-winning actor Tom Hanks announced he and his wife, Rita Wilson, had tested positive for COVID-19.

As we unpacked in the little apartment we’d rented, watching all this unfold, I began to worry we might get stuck in New York for the next month. Feeling helpless, we decided to use our tickets and escape for a few hours with a musical. The next day Broadway shut down.

Betting on my immune system

We were in New York for less than 48 hours, but that was long enough to pick up the virus. We probably contracted it at the show, an adaptation of the movie Mean Girls. (Perfect, right?)

My husband and daughter started feeling sick first – about two days after we got home. My symptoms started two days later. My husband was so convinced we didn’t have COVID-19, because our symptoms didn’t match those we were hearing on the news, he bet me $20.

"Make no mistake, COVID-19 is not just 'a bad case of flu.' It's much worse. Even if you get a mild case, people you infect might not. We can't afford to trivialize COVID-19."

Claire AldridgeCOVID-19 survivor

This was our experience:

- None of us ran a meaningful fever; mine never got above 99.7.

- We didn’t have shortness of breath or tightness in our chests.

- But our muscles and joints ached as if we’d had a brutal workout the day before.

- My husband and I lost our sense of taste and smell, and let me tell you, when food leads with texture it can be pretty unpleasant.

- I was miserable with headaches for five days, and no amount of painkiller helped.

- We also had very little energy – four hours was the longest I could go without a nap.

Our 12-year old bounced back first, and I’m not too proud to say she took care of us, making us lots of tea and toast. Our friends also brought groceries and left them on our porch.

The entire time, I tried to remind myself, “Your immune system knows what it’s doing. It has had evolutionary pressures on it for millennia, and it knows how to react to unknown pathogens.” I just had to trust my immune system.

The fear is real; so is the virus

By March 20, my symptoms had not let up, so I went for a COVID-19 test at a drive-up facility that had just opened at UT Southwestern. Health care workers in full personal protective equipment swabbed the inside of my nose and told me it would be about five days before we’d know the results.

The wait was fairly common in the early days of PCR (polymerase chain reaction) testing for COVID-19. But that stretch of not knowing felt like an eternity – especially when you layer on the fear that the virus was spreading quickly and killing people my age.

Whenever I sensed the slightest tightness in my chest, I began to wonder, “Do I need to go to the hospital? Or am I just anxious because of all the horrible news I’m reading?”

The doctor says I had what would be considered a mild to moderate case of COVID-19: no shortness of breath, no substantial fever, no hospitalization. But looking back, it was still pretty terrifying. I was very sick for nearly two weeks, and the level of discomfort ranks among the worst illnesses I’ve had as an adult (and I had chicken pox when I was 24.)

Make no mistake, COVID-19 is not just “a bad case of flu.” It is much worse. And even if you get a very mild case of the virus, the people you could potentially infect might not.

As a community and a country, we can’t afford to trivialize COVID-19.

Participating in a solution

The first time I heard about convalescent plasma, I was in immunology class. The technique, which has been around for a century, was used to help manage the 1918 influenza pandemic and the Ebola outbreak in 2014.

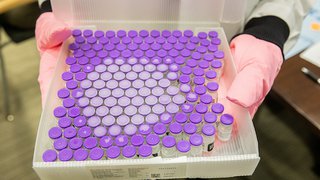

Essentially, it takes blood from recovered patients, separates the plasma, which is typically rich in virus-fighting antibodies, and gives it to people still battling the illness. When the FDA approved an emergency use convalescent plasma program at UT Southwestern, it was an amazing opportunity for me to not just influence and advance a scientific solution for patients, as I do in my job, but to actively participate in the solution.

Of course, there are strict guidelines about who can donate convalescent plasma. You have to be symptom-free for 28 days after testing positive for COVID-19, as I was, or you can participate in serological testing, which can confirm the presence of proteins (antibodies) made by the body’s immune system to indicate prior exposure SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19.

The process to donate plasma can seem slow and no doubt it needs some smoothing out to be offered on a larger scale, but there are some early positive signs. By early May, North Texas had become one of the leading plasma donation sites in the country. And results show that the therapy can be effective, particularly in speeding recovery and increasing the odds of survival for severely ill, hospitalized patients.

Reflecting over 'liquid gold'

Giving blood has never been easy for me because I have tiny, hard-to-find veins.

Donating plasma is even more challenging because it requires a bigger needle with two lumens so the blood and plasma can be separated. (After the straw-colored plasma is removed, the red blood cells are returned to the donor.) The entire process, complete with poking and prodding to find a good vein, lasted about 90 minutes for me. Normally, it takes about 45.

But I didn’t mind. It gave me time to think about everything that has unfolded over the last two months, and especially the people I might be able to help.

The nurses told me that each convalescent plasma donation has the potential to help three COVID-19 patients. Most of those people are hospitalized and probably on ventilators, and most are probably alone without family nearby due to hospital restrictions. All of them are scared.

That could have easily been me or my husband.

Giving back the best way I can

Sitting on a bus for 90 minutes with needles stuck in my uncooperative veins would not normally be the way I’d like to spend a grey Wednesday in May. But if the pandemic has taught me anything, it’s that I miss seeing people and I crave human contact. We all do.

I truly enjoyed talking with my next-door donor neighbor, who was providing a second batch of convalescent plasma. (I hope to donate again in 28 days.) The nurses helped me document the day by taking some additional cellphone photos, and as we chatted through our masks I learned that 16 people had come through this collection site already that day.

I think that number will continue to rise, because donating plasma is empowering – a feeling that most of us have been missing over the course of the pandemic. Certainly, I never wanted to get COVID-19, but I am thankful for the unique perspective it has given me on life and the future.

Every time I see my mom and dad, husband and daughter, I hug them a little tighter.

At work, I feel a renewed sense of urgency to get our science to a point where it can change lives and everyday patient care. (UT Southwestern has already filed several patents for potential therapeutics related to COVID-19.)

And donating plasma, well, it has made me feel more connected to my community. So many people have stepped up to help others during the pandemic, from checking on neighbors to donating masks for frontline health care workers to leaving meals on my front porch.

It’s inspiring, really, and among the many reasons I felt compelled to make this unique contribution.

Donating plasma is just the beginning. But it’s a pretty cool one. Definitely worth a selfie.

And FINALLY, I won a bet with my husband!