After nine months of struggling through an unprecedented pandemic, it’s only natural that people have grown weary of following restrictions and hearing about rising case counts.

But there couldn't be a worse time for a collective sense of COVID-19 fatigue to be setting in:

- The weather is turning colder, which means people are more likely to socialize indoors.

- It’s flu season, which creates increased risks from respiratory viruses.

- Many colleges and schools have resumed in-person learning and campus events.

- Some states have relaxed public health orders and reopened nonessential businesses.

- And Thanksgiving is fast approaching, when families will feel tempted to host indoor gatherings that have the potential to turn into superspreader events.

With COVID-19 cases rising at record rates in the U.S. in late October, now is simply not the time to let our guard down. In fact, we have to strengthen our resolve and remember all that we've learned in the battle against this unrelenting virus.

Let’s take a COVID-19 refresher course, review the facts, and dispel some of the misinformation that continues to spread almost as quickly as the virus.

Coronavirus 101: 5 key facts about the pandemic

1. COVID-19 is a respiratory virus that spreads quickly and easily.

When someone talks, sings, coughs, or sneezes they expel respiratory droplets that may contain viral particles. These particles can be inhaled, particularly when people are in close proximity. Droplets can also land on surfaces and the virus can be contracted by touching those surfaces and then touching your nose or mouth, but that is not the main form of spread. Similarly, smaller aerosols may drift farther away from an infected individual, but they contain smaller amounts of the virus and research suggests they’re not a primary source of transmission.

2. The three W’s work: Wear a mask, wash your hands, and watch your distance.

If everyone covered their noses and mouths with a face mask, it would exponentially reduce community spread. The science is clear on that account. When combined with maintaining six feet of physical distance and washing your hands regularly or using hand sanitizer, masks are the most effective way to protect you and the people around you.

3. Outdoors is safer than indoors.

Research has found the risk of transmitting the virus outdoors is 20 times less than it is indoors. The dynamics of natural airflow and open space make it a much safer option. But masks should still be worn, particularly at outdoor gatherings where six feet of physical distance isn’t always possible.

4. You can be asymptomatic and still spread the virus.

In fact, asymptomatic people account for 40% to 45% of COVID-19 infections. Many young adults and children don’t exhibit notable COVID-19 symptoms, such as fever, headaches, and loss of taste and smell, but studies have shown asymptomatic people can transmit the virus for at least 14 days without knowing it.https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/coronavirus-disease-2019-vs-the-flu

5. COVID-19 is deadlier than the flu.

While COVID-19 and influenza are both respiratory viruses with similar symptoms, the novel coronavirus is at least 10 times more deadly than the flu, according to Johns Hopkins University, largely due to the fact that very few people have built up immunity to it and there is no vaccine yet. While COVID-19 is still being studied, we already know it can spark a cytokine storm in some patients, causing their immune system to shift into hyperdrive and create severe inflammation in vital organs, such as the lungs, heart, and kidneys.

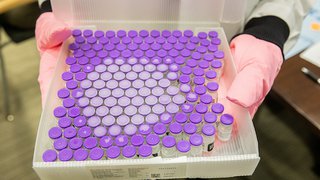

The Making of a Covid-19 Vaccine

Dr. David Greenberg, an infectious diseases specialist at UT Southwestern, explains the complex vaccine development process, and how remarkable it has been to see scientists close in on a COVID-19 vaccine in less than a year.

Clearing up COVID-19 confusion and misinformation

1. Young people ARE at risk of getting sick from COVID-19.

If the 9 million cases of COVID-19 in the U.S. through October have taught us anything, it’s that no particular group is immune from its spread. Initially, people over age 65 and with pre-existing medical conditions were considered to be at higher risk, according to the data. But during the summer months, the incidence of COVID-19 was highest among people ages 20-29, according to CDC research. That group accounted for more than 20% of all confirmed cases.

Research has also shown us that men are more likely to suffer severe COVID-19 complications or death than women, and the virus has disproportionately affected people of color. UT Southwestern is currently conducting a massive prevalence study in Dallas and Tarrant counties to better understand its impact in our community.

2. Wearing a mask will NOT cause carbon dioxide poisoning or oxygen deficiency.

Cloth face coverings and masks do not trap enough carbon dioxide to be harmful. Similarly, any suggestion that masks deprive people of oxygen is unfounded. Masks are very safe when worn properly. Health care workers have worn them for years with no ill effects.

3. Herd immunity is NOT AN OPTION to deal with the pandemic in the U.S.

The term “herd immunity” is used most often when discussing a vaccinated population and an infected patient, for example in recent measles outbreaks. Because there is no COVID-19 vaccine yet, herd immunity proponents are suggesting that natural infection – letting large numbers of people become infected – would ultimately reduce the exponential spread because the virus would have more difficulty finding acceptable hosts.

But a Lancet study suggested that fewer than 10% of people in the U.S. have been exposed to the virus, and there have already been more than 200,000 deaths. Reaching herd immunity would likely require that 40% to 60% of Americans become infected. Achieving natural immunity would come at a terrible cost, often unduly paid by the most vulnerable in our population.

Although some postulate that we could achieve herd immunity by allowing younger and lower-risk Americans to contract COVID-19, that risk is still not zero and the long-term health effects of COVID-19 are still being understood. Additionally, the social patterns and movements of people and families predict that it will be impossible to shield the most vulnerable and allowing the virus to run rampant through the population would risk an uncontrollable outbreak. Herd immunity is most safely achieved through vaccination.

4. A vaccine will NOT mean an instant return to normal.

Several vaccines are in Phase 3 trials and top infectious disease officials believe at least one will be approved for emergency use by the end of 2020, but it will take time to vaccinate everyone, with the high risk healthcare workers and the most vulnerable populations getting access first. Many of the COVID-19 vaccines being developed require two shots, spaced out by 21 to 28 days. Much like influenza vaccines, the COVID-19 vaccine may not be 100% effective, so we may still need to wear masks, wash hands, and keep our distance until community spread falls below an acceptable level.

5. Once you’ve had COVID-19 or a vaccine, it's UNKNOWN if you’ll be immune forever.

Right now, scientists and physicians don’t know exactly how long COVID-19 immunity lasts. There have only been a few recorded cases worldwide of COVID-19 re-infection, which indicates once the body produces antibodies, they should provide protection for an extended period. A study published in the journal Immunity in October showed antibodies lasted at least 5-7 months. New studies also indicate that COVID-19 may activate a different kind of immunity, called T cell immunity, that may last longer.

But it’s too soon to know whether a COVID-19 vaccine will provide long-lasting immunity, like the measles, mumps, rubella shot, or if it will become an annual immunization similar to the influenza vaccine, which changes each year to respond to mutations of the virus.