Navy veteran navigates cancer journey from paralysis to remission

November 7, 2025

Growing up in Dallas, Clinton Adger was in constant motion, whether he was competing in track and field, lifting weights, or enlisting in the military at age 18.

That drive propelled him into an eight-year U.S. Navy career in electronic intelligence. He sailed six of the seven seas, circled the globe twice, and served in high-profile roles with the National Security Agency and Office of Naval Intelligence before leaving the maritime service branch.

Back home in Dallas, the retired petty officer remained active working as an information technology expert and often walked 5-10 miles a day. In his prime at 39, he felt like nothing could slow him down.

But in the summer of 2021, a sudden wave of pain and alarming symptoms brought his active lifestyle to an abrupt halt. Clinton went to a local emergency department with unexplained back and shoulder pain. Symptoms quickly escalated. Within weeks, he couldn’t move his legs and needed a wheelchair to get around.

On his 40th birthday, Clinton was diagnosed with multiple myeloma – a cancer of the blood plasma that had begun to gnaw through his vertebrae. He was two and a half decades younger than the average patient and one of the youngest that Aimaz Afrough, M.D., and her team at UT Southwestern’s Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center had ever treated.

“Clinton was such a good role model for all of us,” Dr. Afrough said. “He did not focus on the negative. He knew this would be a challenging mission, and he was committed to putting in the work.”

Today, Clinton is in remission from cancer. His faith in God is stronger than ever, and he lives a full and active life. He’s an adaptive sports champion. And he has even regained the ability to walk. All of it is a testament to team-based cancer and spinal injury treatment, a strong support network, and the importance of balancing discipline with self-care.

What is multiple myeloma?

When Clinton first heard his diagnosis, he asked the same question many patients do: “What exactly is multiple myeloma?”

A cancer of the blood plasma cells in the bone marrow that normally make infection-fighting antibodies, multiple myeloma causes abnormal plasma cells to grow and multiply out of control, crowding out healthy blood cells.

According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program and the American Cancer Society, the estimated incidence of multiple myeloma in the U.S. for 2025 is 36,110 new cases. As of 2022, about 192,144 people across the nation were living with multiple myeloma. Multiple myeloma accounts for less than 2% of all new cancer diagnoses in the U.S. each year. Many patients live with the early, pre-cancerous stages of myeloma for years with no symptoms.

As the disease progresses, symptoms can include:

- Bone pain, weakness, or fractures

- Fatigue

- Frequent infections

- Impaired kidney function

- Confusion

"When you can’t control what’s happening, challenge yourself to control the way you respond. That’s where your power is."

From the journal of Clinton Adger

Multiple myeloma accelerates the normal breakdown of bone tissue. This can cause osteoporosis that weakens the bone as well as soft spots called lytic lesions. Both conditions significantly increase the risk of fracture.

Up to 80% of patients with multiple myeloma develop bone disease, about 5%-10% have spinal cord compression due to lesions, and 47% experience vertebrae compression fractures.

Multiple myeloma is not considered an inherited or hereditary cancer. However, changes in certain genes that occur during a person’s lifetime can play an important role in how the disease develops.

In about half of patients, these changes involve a gene region on chromosome 14 that helps control how immune cells make antibodies.

While familial clustering and inherited risk alleles exist, most cases are not due to inherited mutations but rather acquired genetic changes in plasma cells.

Black patients are more than twice as likely to develop multiple myeloma compared with white patients. Other risk factors include obesity, alcohol consumption, and exposure to hazardous chemicals or radiation.

Back pain, a biopsy, and a cancer diagnosis

When Clinton first went to the hospital with severe back pain, an MRI showed abnormal density in the fatty tissue around the spine between the T6 and T7 vertebrae of his mid-back. This is typical with discitis, an infection of the cushiony tissue between the vertebrae.

He was sent home with orders for a follow-up MRI and a bone marrow biopsy to rule out other conditions. But he soon returned with worse pain and new weakness in both legs.

“Clinton’s blood work showed high protein levels in his blood, a sign of anemia that zaps your strength,” Dr. Afrough said. “A bone marrow biopsy led to the diagnosis of multiple myeloma and showed that the cancer had infiltrated about 30% of his plasma cells – the immune cells in the blood that make antibodies to protect the body from infections.”

Subsequent imaging showed the cancer had weakened Clinton’s vertebrae, leading to a compression fracture that damaged his spinal cord. That left his legs partially paralyzed and caused nerve pain and spasticity.

“One night I went to sleep and woke up unable to walk or go to the restroom by myself,” Clinton recalled. “My doctors said there was a chance I might not walk again. But I didn’t want to accept that diagnosis…

“I kept having dreams of running, walking, and doing things with my son,” he said.

“God is not punishing you; he is preparing you. Trust his plan, not your pain.”

From the journal of Clinton Adger

Finding a path forward

At the Dallas VA Medical Center, Clinton began a course of radiation therapy that targeted the T3 to T9 vertebrae – from about the base of his neck to below his shoulders. His cancer care team included specialists from UTSW’s Simmons Cancer Center, who helped him understand his diagnosis and treatment options.

There was a lot to take in. Clinton found an outlet to help him deal with his emotions.

“I have a journal that I’ve kept since the first day,” he says. “Everything in the beginning was just so dismal. But the entries became more hopeful as my treatment progressed.”

Sometimes, he would find himself awake at 3 in the morning penning letters to himself. One night he wrote in big block letters:

“God is not punishing you; he is preparing you. Trust his plan, not your pain.”

That mantra, which he now shares with others, helped Clinton navigate a four-year voyage to rebuild his immune system and reclaim his life.

All hands on deck — with a new commanding officer

The VA care team eventually recommended that Clinton get an autologous stem cell transplant. In this treatment, high-dose chemotherapy is used to destroy as many myeloma cells as possible, and his own previously collected healthy stem cells are then returned to help his bone marrow recover.

For multiple myeloma, specialists prefer an autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), which uses the patient’s own stem cells instead of donor cells. This option reduces the risk of graft-versus-host disease, a complication in which the body doesn’t recognize transplanted tissue and attacks it.

ASCT is not available at the Dallas VA. There was talk of transferring Clinton to a VA in Seattle. But then a care coordinator suggested UT Southwestern, which is ranked by U.S. News & World Report as one of the nation’s top 20 hospitals for cancer care. As the only National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center in North Texas, Simmons Cancer Center offered Clinton access to advanced treatments and a highly specialized care team.

Clinton scheduled an appointment with Dr. Afrough, an expert in multiple myeloma and other plasma cell conditions.

“I was so nervous. I asked my mom and both my sisters to come with me,” Clinton recalled. “Dr. Afrough came in and said, ‘This is my team, and this is what we’re going to do.’ I knew right then that putting my care in her hands was the right plan.”

Related reading: Young newlywed, UTSW cancer team wage 'Infinity War' on stage 4 lymphoma

"Stop trying to calm the storm. Calm yourself … the storm will pass."

From the journal of Clinton Adger

Preparing for transplant: A team effort

As soon as Clinton was accepted to the transplant program, the UTSW stem cell coordination team members went into action, mobilizing their expertise and resources. Clinton’s transplant preparation began with several months of induction therapy.

“Induction is typically a combination of three or four medications, and we do an extensive evaluation of the heart, lungs, and other organs and check for various infections,” Dr. Afrough says. “Induction therapy helps shrink the myeloma, making it easier to collect stem cells and set the stage for the high-dose chemotherapy that follows, which will destroy remaining myeloma. The stem cells are then returned to help the bone marrow recover.”

Throughout his treatments, Clinton relied on help and motivation from his extensive network of family, friends, and church congregants. His sisters, Ramona and Ladonya, kept him physically comfortable and emotionally engaged. He says his relationship with his son, Chase, now an 11-year-old honors student, motivated him to carry on.

His mom gave him the kind of tough love that only a mother can.

“She told me I couldn’t sit and feel sorry for myself, that I had to get up and get going,” he recalled. “She was there for the late nights, reminding me that where I was then was where I needed to be.”

Clinton responded well to the medications, with about a 90% decrease in his disease markers. He was cleared for the next step: harvesting the stem cells that would be used in his transplant.

‘Like getting an oil change’

Stem cells are the body’s “starter” cells, capable of becoming many different types of blood cells. In the bone marrow, these cells grow into mature red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, or plasma cells. All of them are essential to the immune system.

Before his stem cells were extracted, Clinton received shots of growth factors for five days. These medicines help “mobilize” the stem cells from the bone marrow into the bloodstream, where they can be collected.

Stem cells are collected through a painless procedure called apheresis – the same technology used for donating plasma. A thin catheter is inserted into a vein in the upper chest, then connected to a machine. This device extracts the stem cells from the blood. The remaining parts of the blood are circulated back into the patient’s body through another branch of the catheter.

“When you first walk into that room, the machines are a bit intimidating. But then they explain how it works, and you put it all together,” Clinton says. “You have one cylinder pulling blood and removing impurities, and another one is putting it back. It’s like getting an oil change.”

Collecting stem cells for ASCT typically takes about four to six hours a day over one to three days. After each session, lab technicians count the number of stem cells retrieved. They are frozen and stored in a container cooled with liquid nitrogen.

A few days before the ASCT, Clinton received a high dose of chemotherapy to eliminate any residual myeloma and suppress new production of bone marrow. The countdown began for Day Zero – transplant day.

"You may have to fight a battle more than once to win it!!!"

From the journal of Clinton Adger

A new beginning

Clinton vividly remembers August 17, 2022. As he waited with his mom and sisters before his transplant, he managed his nerves by cracking jokes.

“They gave me the pre-medication to help prevent reactions during the treatment, and then they started,” Clinton says. “It was more like a transfusion than a surgical procedure. Dr. Afrough called it my new birthday.”

It was his second chance at life. Seven days later, he began losing his hair: First his beard, then the hair on his head came out in patches.

“Even though I looked different, just knowing I had the stem cells made me feel better,” he says. “It was working inside my body. I knew my blood counts were going up.”

Related reading: Chuck’s story: Adventure and advocacy years after historic stem cell transplant

Rebuilding body and spirit

Inpatient rehabilitation

Patients often go home after engraftment following their stem cell transplant. But because myeloma had limited Clinton’s mobility, he transitioned to inpatient rehabilitation at UTSW’s Zale Lipshy Pavilion. There, he worked closely with an extensive supportive care team, including:

- A Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation physician with extensive training in helping patients regain function and developing personalized treatment for cancer-related pain

- Physical therapists for rebuilding strength and mobility

- Professionals in psychiatric oncology and social work

- Doctors of Pharmacy and other pharmacists with advanced training

“The supportive care team looks holistically at what can be done to help the patient go through the expected recovery and any complications,” Dr. Afrough says. “It’s a collaboration between a lot of disciplines, everyone coordinating their expertise to help patients with complex needs.”

"Your soul is attracted to people the same way flowers are attracted to the sun - surround yourself only with those who want to see you grow."

From the journal of Clinton Adger

Outpatient rehabilitation

As Clinton approached his discharge from inpatient rehab, he was strong in body and mind, but he was compelled to continue his journey.

“I kept saying, ‘How can I do more stuff? I want to try. I want to do more,’” he said.

One of his trainers at Zale Lipshy suggested an eight-week outpatient rehabilitation program through the Adaptive Training Foundation in Carrollton. The organization’s motto of “Defy Impossible” mirrored Clinton’s commitment to rebounding both physically and mentally. He submitted his application and toured ATF’s gym. He was impressed with what he saw: a community of people working together to break through limitations.

“When I left UTSW, I was still in my wheelchair,” Clinton said. “The first thing you lose after not walking for a while is confidence in yourself – even taking that first step.”

Clinton’s trainers challenged him to verbalize and confront his fears.

“They got me using the walker, and they were right there when I took those first couple of steps,” Clinton says. “By the end of week three, I was walking with the cane. I was moving slow, but I was so proud.”

Clinton’s trainers, and his military discipline, helped him stick with the physical therapy at home. In fact, he kept his amazing progress a secret from his family for a time.

When his mom called one night to tell him she was on her way over to help with dinner, he decided to start without her.

“When she got there, I was standing at the stove with the wheelchair behind me,” Clinton said. “The door opens, and I just kind of look, and then she looks at me.

“‘Well now, when did all this start happening?’” Clinton recalled her shouting.

His reply? “Dinner’s almost done.”

Later that evening, after a celebratory call on speaker phone with his sisters, Clinton stood at the sink washing dishes for over 30 minutes. That’s when he knew he was regaining his independence. At the end of his eight-week program, he began volunteering at ATF. He now mentors other veterans who’ve had spinal cord injuries as well as firefighters and first responders – proof that healing can lead to purpose.

"You can either hurt now from trying or you can hurt later from never having tried."

From the journal of Clinton Adger

Skiing, self-care, and hope

On the medical side, Clinton has transitioned to maintenance therapy. He takes a low‑dose oral chemotherapy medication daily and receives a monthly injection to boost his immune system. His recent bone marrow biopsies showed no measurable signs of cancer, a status called “unquantifiable” – and a word he loves to hear.

He and Dr. Afrough have already mapped out next steps in his care.

“She made me pinky-promise,” Clinton says with a smile. “If my numbers go up at any time, I’m coming back in with no fussing and no complaining, just moving forward.”

When he’s not working out in the gym or volunteering at ATF, he’s pursuing new athletic activities.

“Last year, I got the chance to go skiing at Lake Tahoe,” Clinton says. “At first, everyone is flying past me down the slopes, and I thought, ‘I don’t understand why you people want to go this fast on snow.’”

He quickly mastered the basics, and now he’s looking forward to more skiing adventures through the adaptive sports organization High Fives Foundation. This California-based nonprofit helps injured veterans and athletes regain their joy through outdoor sports.

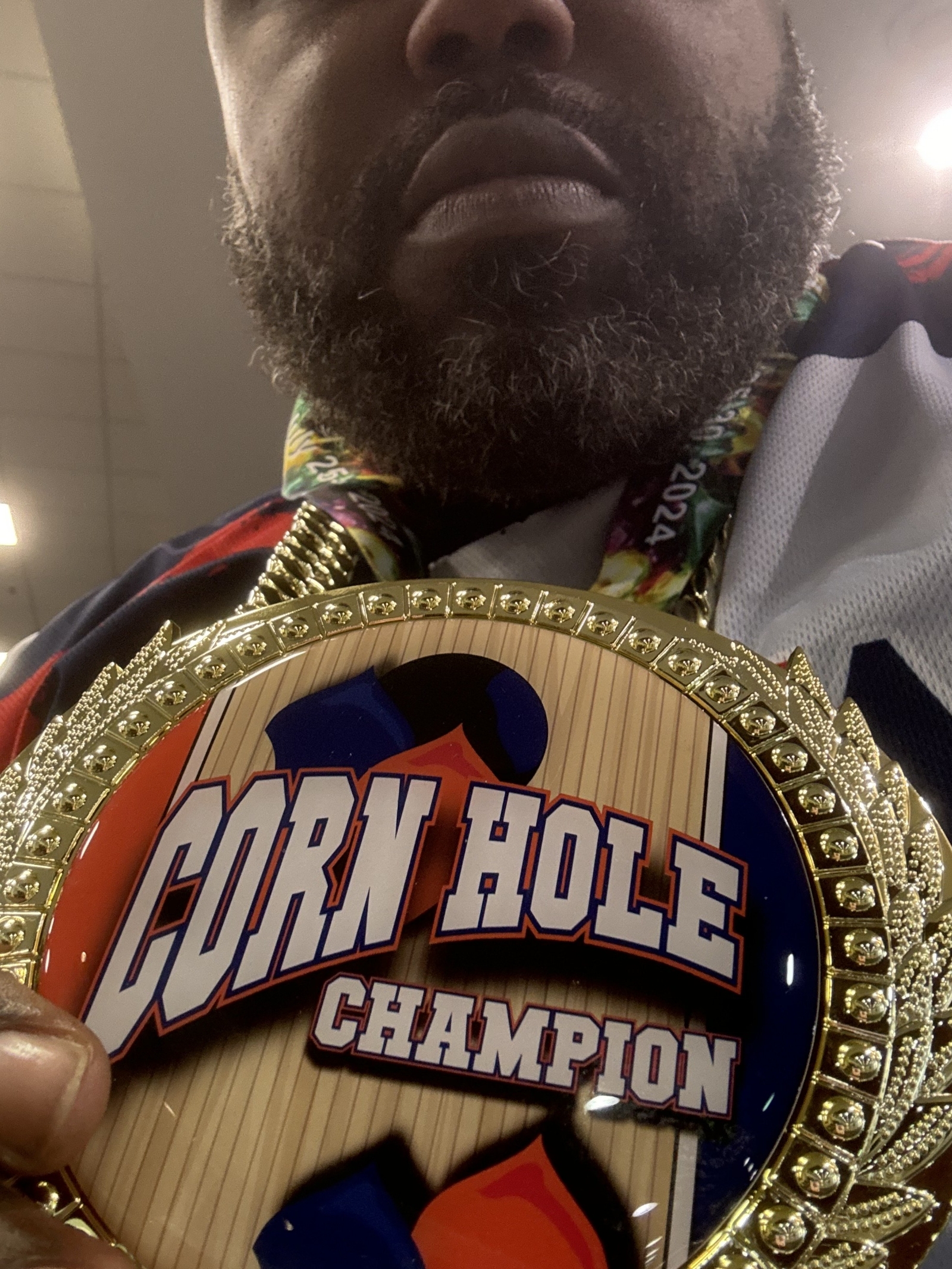

Clinton has also discovered a passion for cornhole, a beanbag tossing game that’s evolved into leagues and international competitions. Through the Lone Star chapter of the Paralyzed Veterans of America, he teamed up with a fellow veteran to compete in the 2024 National Veterans Wheelchair Games in New Orleans. Together, they won gold in the paraplegic division – his first medal and a tangible symbol of how far he’d come.

When Clinton talks with other cancer survivors and rehabilitation patients, he stresses the need for self-care and patience.

“This journey is one hell of a ride,” he said. “There are so many ups and downs, and you’ve got to be gentle with yourself.”

For Clinton, it’s about finding joy in moments big and small.

“So, if a needle has to go in your stomach,” Clinton says, “you can decide that ice cream can go into your stomach, too!”

To talk with an expert about multiple myeloma or stem cell transplants, make an appointment by calling 214-645-4673 or request an appointment online.