Effective OCD treatment to quiet intrusive thoughts, control repetitive behaviors

September 23, 2025

Have you ever spent an hour agonizing over whether you turned off the lights before leaving the office? Tapped a doorknob exactly six times before entering your home because it felt wrong not to? Or picked up a kitchen knife to cut vegetables and had an intrusive thought of harming someone, followed by a wave of shame?

These scenarios are classic signs of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), a neurobiological condition related to overactivity in specific circuits of the brain.

With OCD, obsessive and intrusive thoughts manifest as mental actions or compulsions, such as tapping or counting, that are meant to control or neutralize distress. Patients are often acutely aware of their unwanted thoughts and repetitive behaviors. That cycle, as well as the perceived social stigma that comes with it, can weigh down a person’s quality of life. It can lead to feelings of isolation, which can make symptoms worse.

But there is good news. OCD is common, it’s not your fault, and it’s treatable. More than 8 million U.S. adults live with the disorder. That equates to about 158,000 North Texans, making OCD the fourth-most common mental health diagnosis.

Despite its prevalence, OCD is frequently misunderstood and undertreated. About 90% of patients have an additional mental health condition, such as anxiety or a mood disorder, with overlapping symptoms. And getting the proper diagnosis and care can be challenging if the health care provider you choose does not specialize in OCD.

UT Southwestern is filling that gap with a dedicated OCD treatment service from our psychology and psychiatry providers within the Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute. Our clinic brings together experts in OCD diagnosis, therapy, medication, and advanced treatment options to provide personalized, well-rounded care for OCD. For many patients, just getting an accurate diagnosis and the validation that they aren’t alone takes a significant weight off their shoulders.

What causes OCD?

Scientists used to think OCD was a result of childhood trauma. Now we know it is related to overactivity in the cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical loop, a neural circuit that is responsible for habit formation, movement, and reward functions in the brain.

That loop fires much more frequently and intensely in people with OCD. More commonly this is a biological abnormality that is inherited genetically and is not environmentally related. In rare instances, OCD symptoms can be related to exposure to specific viruses or bacteria, such as Streptococcal infection. Symptoms can increase in intensity as a result of a traumatic event, high stress, or social isolation.

Most cases of OCD are diagnosed in young adulthood between ages 18-23, but in some instances early signs of OCD can be seen in childhood. Women are a little more likely than men to be diagnosed with the disorder.

Living with OCD can shape your personality and vice versa. Some people cope by masking their symptoms or only performing rituals in privacy. Others use their need for perfection to achieve personal and professional goals.

Obsessive compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) is a personality disorder marked by pervasive perfectionism and control, while OCD is a clinical syndrome defined by distressing obsessions and compulsions. The two can co-occur but are distinguished by the presence of true obsessions and compulsions in OCD, which are absent in OCPD. These patients feel bound to a particular schedule and certain ways of doing things. They often micromanage and double- or triple-check their work. People with OCPD are less aware of their obsessive and compulsive tendencies and are more prone to having OCD – at least 20% of OCPD patients have both conditions.

What are the symptoms of OCD?

OCD is far more complex than a penchant for tidiness and organization. It is a collection of obsessions and compulsions that can range from mildly annoying to significantly time-consuming and socially crippling.

Obsessions are persistent, intrusive thoughts that are illogical, distressing, and out-of-character. Patients ruminate over a particular thought and cannot eliminate it through logic and willpower alone. Common obsessive symptoms include having:

- Taboo thoughts, such as explicit or violent acts you would never carry out

- Taboo sexual thoughts that create distress

- Dread about an illogical future state, such as a hair straightener in the microwave starting a house fire

- Obsessions with saving or collecting items

- Hyperfocus on certain numbers or colors

- Chronic doubt about completing tasks and the need to go back and check

- Need to follow a mental ritual before proceeding with one’s day

- Fear of contamination, such as coming in contact with germs

- Worry about forgetting or losing things

Compulsions are the repetitive behaviors or mental steps a person takes to neutralize the distress caused by an obsession. Patients describe these rituals as necessary to feel “normal,” “right,” or “balanced.” Common compulsion symptoms include:

- Having to tap an object multiple times before moving on

- Counting and making patterns in one’s environment, such stepping on an even number of sidewalk cracks while jogging

- Restarting the tapping or counting cycle at zero if interrupted

- Repeatedly checking whether a task, such as turning off the oven, has been done

- Seeking frequent reassurance from others that they are still liked or cared for

- Repeating words or phrases to oneself, often silently

- Relentlessly cleaning or arranging until everything in a space is “perfect,” going well beyond what is necessary

- Excessive handwashing due to fear of germs

Acting on compulsions can eat up hours of time and can become socially disruptive, resulting in a person appearing disorganized or chronically late due to their rituals.

OCD may be more common than you think. Comedian Maria Bamford has been public about her obsessions, calling OCD “exhausting” while making light of her symptoms during her stand-up routines. Actor Howie Mandell says he can’t remember how long it’s been since he shook someone’s hand and has referred to the obsessive-compulsive cycle as a “brick wall.” Others who have been open about their experiences with OCD include singer and actress Ariana Grande, Harry Potter actor Daniel Radcliffe, and soccer star David Beckham.

“Many patients with OCD find a strong sense of relief in their diagnosis and starting therapy. It loosens the hold of the shame and stigma that keep them isolated. Normalization is a critical first step in healing.”

Kipp Pietrantonio, Ph.D., ABPP, UT Southwestern OCD Therapy Lead and Director of Psychological Services

How is OCD diagnosed?

It's crucial to differentiate OCD from other conditions with similar symptoms, like anxiety disorders. While anxiety is at the core of OCD, the defining feature of OCD is the presence of obsessions and compulsions that disrupt life.

People who have lived for years with the disorder can become experts at masking their symptoms to fit in socially and professionally. OCD can be more complex when co-morbid with other common disorders such as ADHD, depression, or generalized anxiety.

So, diagnosing OCD is a multistep process that requires specialized evaluation. At UTSW, the first step is a discussion about which symptoms you have, how often they occur, and how much time you spend in the obsession-compulsion cycle each day. We’ll talk through a list of the 50 most reported symptoms – yes, that many! It’s not uncommon for patients to relate to many of the items across the lifespan. As part of this survey, we can also uncover OCD spectrum disorders, such as Tourette syndrome, tics, trichotillomania (hair pulling), and excoriation (skin picking).

In general, patients diagnosed with OCD meet these criteria:

- Spending an hour or more a day in the obsession-compulsion cycle

- Being unable to break the cycle, despite awareness of their symptoms

- Getting no lasting satisfaction from completing compulsions

- Having disruptions in daily life due to their symptoms

Getting an OCD diagnosis is often a lightbulb moment for patients. Many tell us, “I thought I was the only one struggling with these thoughts or behaviors!” Shame often keeps OCD hidden and untreated, yet the more shame patients feel, the more intrusive their thoughts tend to become. Receiving a diagnosis validates their experience and helps reduce stigma. For many, that sense of recognition jumpstarts healing even before their treatment plan officially begins.

How is OCD different from anxiety?

Anxiety is frequently environmental. When you lock a door, it’s normal to double-check the lock. A person who was robbed in the past, for example, may associate an unlocked door with that bad memory and have a panic attack. OCD is generally not environmental. It is a rogue brain signal that creates an intense urge to check and re-check the lock, often a specific number of times, with no associated fear from a past experience. Often, when a patient is asked why they are doing a compulsion, they can’t produce a logical answer to connect the excessive checking action with the door lock itself. This is called cognitive dissonance, and it’s common in OCD rituals.

What are the treatment options for OCD?

UT Southwestern is a research-driven health center. That means our patients get access to gold-standard therapies and the latest treatments, often before they’re widely available to the public. It also means we can offer flexible options based on patients’ preferences and ability to participate in treatment.

Every patient’s case is reviewed by a team of specialists who co-create a personalized care plan that typically starts with treating OCD behaviorally rather than turning immediately to prescription medication.

Behavioral health therapy

We encourage all patients with OCD to participate in therapy. Exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy is the first step. It directly targets the cycle of obsessions and compulsions, updating the brain’s circuitry and giving patients a new sense of control and freedom.

The patient is gradually exposed to their fears or obsessions and supported to avoid engaging in their usual compulsive behaviors. The goal is to train the brain to tolerate the obsession without performing the compulsion.

For example, a person with a hygiene obsession may be asked to touch the therapist’s laptop without washing their hands after. They’ll progress to touching a doorknob, then a public elevator button, and so on. As their brain accepts that nothing catastrophic happens, it starts to break the obsession-compulsion cycle.

ERP requires courage and commitment from the patient, and it is shown to be highly effective in as little as a few months. Research has shown ERP is the front-line treatment and can be more effective and longer-lasting than medication alone. Most research indicates that a combination of medication in conjunction with ERP produces the best outcomes for patients.

Habit reversal therapy (HRT) can also be used to treat certain OCD-related conditions such as trichotillomania (hair pulling) and excoriation (skin picking). This treatment focuses on increasing awareness of a compulsion and then replacing it with a competing, less disruptive behavior, which helps to gradually rewire brain circuitry. For example, a patient with a facial tic such as frequent blinking, lip licking, or touching their face would work through a structured step-by-step program to recognize the urge, practice alternative responses, and ultimately reduce the frequency of the compulsive behavior.

As with any type of behavioral change, having a strong support system has a strong impact on treatment success. Patients whose loved ones and friends help them avoid isolation and change their habits tend to have better outcomes.

Medication

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRIs) medications such as fluoxetine (Prozac), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluvoxamine (Luvox), and sertraline (Zoloft) may be beneficial along with therapy. About half of patients with OCD respond to medication, and those patients may get up to a 40% reduction in symptoms. For some, it’s enough to take the edge off the distress they feel from the obsession-compulsion cycle.

For OCD, SSRIs are often prescribed at higher doses than for depression – sometimes double the dose to reduce symptoms. It can take two to three months for patients to notice a difference. Other medications such as clomipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant, or antipsychotic medications such as risperidone or aripiprazole may also help reduce patients’ symptoms enough so that they can more comfortably participate in therapy.

Advanced treatment options

These treatments are typically reserved for a person who has failed to respond to a comprehensive course of medication and therapy:

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation: A non-invasive procedure that uses a targeted magnetic field to stimulate dysfunctional nerve cells in the brain. Surgery is not needed, and it can result in about a 50% chance of controlling OCD symptoms.

- Deep brain stimulation: A surgery in which a device similar to a pacemaker is implanted in the brain to deliver electrical signals to help regulate misfiring brain circuits. UT Southwestern is one of only a few places in Texas to offer this treatment.

- Anterior capsulotomy or anterior cingulotomy: A more invasive surgical procedure where a neurosurgeon removes or creates small lesions in a small portion of dysfunctional brain tissue.

Related reading: TMS: How specialized magnets relieve medication-resistant depression

Living with OCD can feel overwhelming, but it is also one of the most treatable mental health conditions. With an accurate diagnosis and personalized care, you can disrupt the obsessive-compulsive cycle and reclaim the freedom, control, and time you’ve been missing out on.

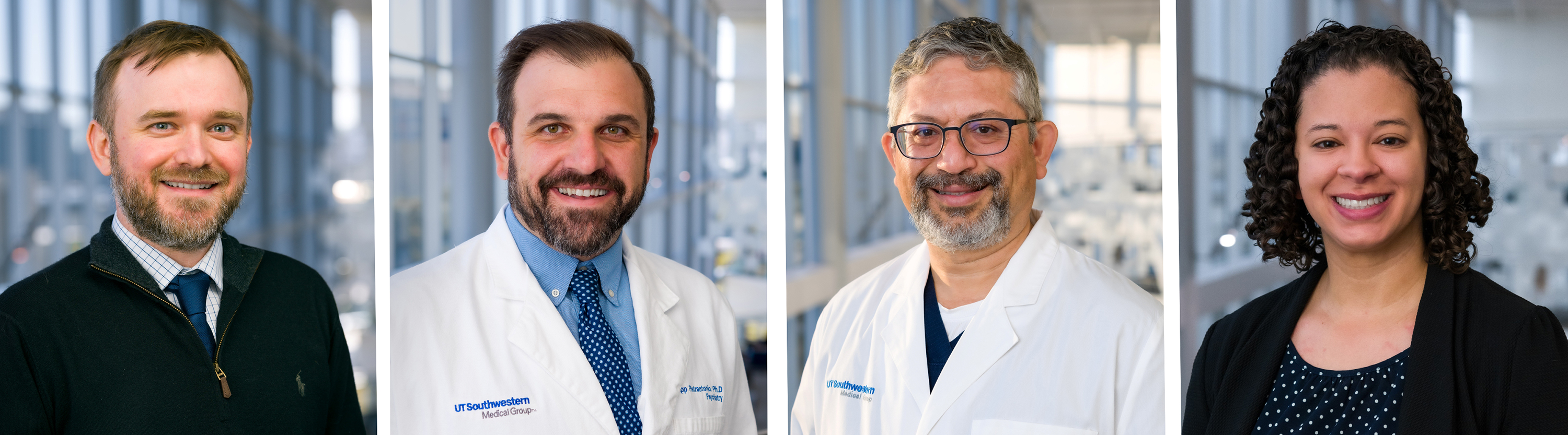

Meet the team

UT Southwestern has launched a clinical care team within the Department of Psychiatry that has expertise in treating OCD. Patients will undergo a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation to determine what type of OCD they have and where they fit on the OCD spectrum. The interdisciplinary team will then decide on the best course of treatment. Regular meetings among the entire team will focus on patients' progress to ensure they are getting the care they need.

Team members involved in treating patients with obsessive compulsive disorder are (from left) John Dykema, M.D., Clinical Assistant Professor; Kipp Pietrantonio, Ph.D., Clinical Assistant Professor and Director of Psychological Services for University Hospitals and Clinics; Collin Vas, M.D., Clinical Associate Professor; and Courtney Sanders, Ph.D., Clinical Assistant Professor.

To talk with an expert about obsessive-compulsive disorder treatment, make an appointment by calling 214-645-8500 or request an appointment online.