Keep pushing. Do a little more. Keep getting better. People who train at elite levels of athletic competition know the value of continuous improvement. They’re motivated by a drive to test – and exceed – their limits.

That’s what motivates me, too. My colleagues and I are driven to better understand the heart. How does it work? What causes it to not work? How can we make it work better?

In our most recent study, we’re reaching back in time to expand on data from our landmark Dallas Bed Rest and Training Study. We want to learn more about how exercise can help keep the heart young, not only in elite older athletes like 74-year-old Dallas marathoner Rio King but also for average adults.

Decades of research on fitness and exercise

I was just 10 years old at the time, but this study formed the basis of much of our knowledge of how the body’s circulatory system adapts to changes in physical activity. In fact, NASA has made great use of the data from this study, because the effects of bed rest on the body are so similar to the effects of spaceflight:

In the 1960s, my mentors Jere Mitchell, M.D., and Gunnar Blomquist, M.D., along with Bengt Saltin, M.D., conducted the Dallas Bed Rest and Training Study. The researchers enlisted five healthy male volunteers in their 20s to go on bed rest for three weeks and then put them through physical training for two months.

- Loss of strength and endurance

- Shrinking of the heart

- Shrinking/weakening of the muscles and bones

We’ve been building on that study ever since. Back in 1996, my colleagues and I found those same five volunteers and brought them back to Dallas – 30 years after the study. In terms of their cardiovascular fitness, all of the volunteers were in better shape than they’d been right after the period of bed rest. Three weeks of lying in bed were worse for these participants’ ability to do physical work than the next three decades of aging.

We followed this discovery with studies showing you could prevent some of the ill effects of bed rest on the heart if you exercise while you’re in bed. For example, one study had volunteers ride a supine bike, also known as a recumbent bike, for 90 minutes per day while they were in bed rest. This was quite effective at preventing many of the cardiovascular changes but was very time-consuming. We also tried running on a treadmill while lying down by using a large vacuum chamber to create a gravity-like effect and suck the volunteers down onto a vertically placed treadmill platform. This approach was also effective, though it was awkward.

Most recently, we turned to one of my favorite exercises: rowing. The volunteers could do this sitting down. It was remarkably effective (rowing is like weight training for the heart) for both the heart and the muscles, and it has become one of our preferred strategies to avoid or reverse deconditioning from almost any cause. Indeed, NASA is currently planning to use a rowing-based countermeasure for the new Crew Exploration Vehicle (Orion)that may end up taking astronauts to Mars.

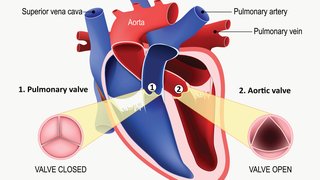

Next, we looked at whether a lot of the changes in the heart we had previously thought were due to aging were actually due to deconditioning – not getting enough exercise over the years. These changes include shrinking and stiffening of the heart muscle, resulting in the heart not filling and pumping as well as it could when it was younger.

We compared older adults who lived sedentary, or inactive, lives but were otherwise healthy with masters athletes – people in their 60s or 70s who had trained at high levels for much of their lives for elite competition and remain active today.

The hearts of our sedentary seniors were what we normally would expect from adults of their age. But the hearts of the masters athletes were indistinguishable from those of healthy 30-year-olds. So some of the heart changes we previously had thought were just part of getting older actually were due to the heart not getting enough exercise.

That’s a huge discovery: Exercise can keep the heart young. But we needed to learn more. When in the aging process does the heart start to shrink and stiffen? How much exercise do you need to hold off those changes?

With the help of our colleagues at the Cooper Clinic, we gathered a new group of study participants to help us answer that question – including 74-year-old Rio King, who, as of December 2016, held the record for the most consecutive Dallas Marathon completions. Rio finished third in his division in the December 2016 Dallas Marathon, completing the race in about six hours.

Testing the limits

Rio’s been running for nearly 50 years. He started running in his late 20s. “I wanted to see what some of my limits were,” he explains. “When I turned 30, I set running the marathon as a test for myself, because I’d been training for summertime track programs.”

Rio liked the challenge of running and stuck with it. “I took to running a lot during the 1970s and ’80s, into my mid-50s, because I was still competitive,” he says. “I wasn’t ever at the top of the stand, but I could occasionally get up there with the top runners in my class. It was a pretty healthy lifestyle. I’d run track in the summertime, and at the end of the summer, I’d start training for marathon season.”

Rio heard about our study through a newspaper article and from a running friend. It was right up his alley with his interest in collecting data on his own performance over time. We put Rio and each of the other study volunteers into a device we built for our NASA studies that uses lower-body negative pressure. Rio says he “felt like an astronaut” when he got in the device. “This was a new frontier for me,” he adds, chuckling.

The device pulled blood from their hearts and into their feet to unload the heart. Then we stretched the heart by pumping in saline and measured the heart’s level of elasticity – its ability to stretch – with a catheter we had implanted in each volunteer. This is a safe procedure that I’ve tested on myself, and it provided remarkable results.

We found that exercising four to five days a week leads to hearts that are almost as youthful as those of the elite masters athletes. And in another study we just finished, we found that people up to late middle age – from age 40 to about 64 – actually can reverse the effects of aging on the heart with enough exercise.

How much is enough exercise for heart health?

I talk to my patients regularly about this, and I’ve written about it before in this May 2016 blog article. In order to maintain heart health or reverse damage done from the aging process, you need to exercise at least four to five days per week. Those days should include:

- At least one day per week of a low- to moderate-intensity activity that lasts at least an hour and that you enjoy, such as playing tennis, taking a brisk walk, square dancing, or taking a Zumba class

- At least one day per week of a high-intensity workout, such as high-intensity interval training

- At least two to three days per week of moderate-intensity training

- Strength training on at least one of those days

Exercise needs to be part of your personal hygiene, like brushing your teeth or taking a shower. It can’t just be something you add on as an afterthought “when you have time.” It’s too easy to let it slip. One important note: If you have a heart condition, work with your doctor to develop an exercise program that’s safe and appropriate for you.

The importance of our study volunteers

None of what we’ve learned would be possible without the help of our study participants. We have to be able to measure and observe the changes our experiments have on the heart and the rest of the cardiovascular system.

Why would otherwise healthy people allow us to do this? As Rio explains, “I wanted to help out. I don’t think there’s a large population of older athletes like me to test, so I was, frankly, proud to be invited to help. My participation, I hoped, would help others – sort of a philanthropic contribution and maybe contribute to the future of medicine. I’m proud to offer something if it’s of use.”

I think most people, like Rio, have a desire to help others, and studies like this are a great way to do that. We’re learning about the science of the heart’s health and fitness, and what we learn can teach doctors everywhere about new standards of care. That’s a big thing to be a part of.

I also think the willingness of study volunteers to participate is a show of their trust in us. They know we’ll keep them safe, and they get the chance to learn a little more about themselves and what they can do to be healthier in the process.

“It’s a highly competent team that has worked with the elite and the world’s best,” Rio says of the doctors and scientists conducting our study. “To put yourself in their hands is a privilege.”

Next heart study reaches new frontiers

Most of the research we’ve done up to this point has been in people with healthy hearts, or comparing people with healthy hearts to those with unhealthy hearts. In our new study, we hope to take the lessons we’ve learned through our previous research and apply them to people with or at substantial risk for heart disease.

In this new study, funded by the American Heart Association, we’re going to research whether we can improve the heart health of people with left-ventricular hypertrophy. This is a condition in which the left pumping chamber of the heart (the ventricle) becomes thickened, which causes the ventricle to be stiffer and perhaps pump less effectively. We’ll put study participants on a yearlong training program to see if we can reduce the thickening in their hearts and lessen their stiffness in order to prevent heart failure later in life. We’ll also examine whether being overweight or obese factors into the heart’s thickening process.

As of January 2017, we’re recruiting participants for this study. Our ideal study participants include men and women who are:

- Diagnosed with left-ventricular hypertrophy (likely because of hypertension, or high blood pressure)

- Middle-aged

- Overweight or obese

Please call research nurse Margot Morris at 214-345-4629 if these categories apply to you and you’d like to help us with our study. It’s the next step in our work to improve heart care for everyone.