Complications of COVID-19 can affect the entire body – from the lungs and liver, to the heart and brain.

The "cytokine storm" effect – the body's excessive immune response in its attempt to fight off the novel coronavirus – has been particularly well-documented in cardiovascular circles, with studies showing that heart damage can linger months after respiratory symptoms resolve.

Heart damage from COVID-19 can include inflammation and fluid buildup (known as edema), as well as "broken heart syndrome" and blood clots. These factors are concerning for all patients, but athletes may be a high-risk group for heart damage due to the cardiovascular demands of vigorous exercise.

Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) consists of the basics for athletes: wash your hands, physically distance, wear a mask, and don't play if you are sick. As high school, college, and professional sports have resumed in recent weeks, institutions, athletes and their parents are looking for additional assurances and advanced cardiovascular screenings to determine when athletes can safely return to play after COVID-19 infection.

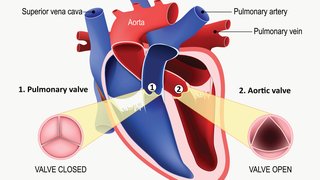

Under consideration is cardiac MRI, an imaging technique that generates 2D and 3D pictures of your heart tissue. Recently, a study published in JAMA Cardiology suggested that cardiac MRI may be useful to determine whether student-athletes' hearts are healthy enough to return to the field of play.

We use cardiac MRI in the clinical setting to diagnose heart function, scarring and inflammation. However, preliminary data suggest that cardiac MRI is not ready for prime time as an effective tool for this particular use.

What to know about the study

Researchers examined 26 patients, all of whom had recently recovered after testing positive for COVID-19. None of the students had been hospitalized with the illness. Some had experienced mild symptoms, while others were asymptomatic.

Of these student-athletes, 15% were found to have edema – fluid buildup in the myocardium, the muscular tissue of the heart – and were felt to have myocarditis, which includes inflammation of the myocardium. Another 30% had evidence of myocarditis without edema.

Edema is an acute finding, which means if you have it, it's likely due to a current or recent condition. Myocarditis, however, can linger after an illness subsides. For an athlete, having both findings is more concerning.

Since this virus is new and this is our first major sports season since the "long haul" of the pandemic, we don't have enough data yet to make sweeping recommendations regarding how much edema/inflammation is acceptable and how long players should be sidelined after COVID-19 infection.

Data from previous respiratory illness outbreaks such as influenza tell us that heart inflammation typically goes away over time. Treatment, if necessary, may include steroids, ACE inhibitors, or beta blockers. Still, patients may rarely be left with scar tissue that can cause lifelong cardiovascular deficits depending on the volume and location of the scar tissue. Unfortunately, there is currently no way to safely remove scar tissue from a patient's heart.

Several similar studies have surfaced over the past months as we learn more about COVID-19. However, most note the limitations mentioned in this study, which suggest much more data are needed to implement cardiac MRI for return-to-play protocols.

Articles from our physicians

How the new blood pressure guidelines can help your heart health

September 30, 2025

Fetal echocardiogram: What to expect

August 7, 2025

Focusing on 10,000 steps a day could be a misstep

August 1, 2025

Limitations of cardiac MRI studies with COVID-19

Small patient populations

The aforementioned study included just 26 patients across five cardio-intensive sports: football, soccer, lacrosse, basketball, and track. Other studies have also included limited patient populations.

Some have questioned the thresholds to define “abnormalities” in this MRI report. Also, the MRI findings differ from those reported in autopsy studies, in which evidence of cardiac involvement is less frequent.

To create new standards of care, we would need data from hundreds of patients at different activity levels, and we would need to track them over time after they have had COVID-19.

Lack of cardiac baselines

Most student-athletes have not had rigorous cardiac testing before. They may have scar tissue from old myocarditis or new inflammation due to a condition not related to COVID-19. A number of ailments, including lupus and influenza, can cause myocarditis.

However, MRI is not designed to function like a CT scan. Though a CT scan is faster, it is designed to provide images of vessels, tissues, bones, and organs. MRI is designed to determine whether there are abnormal tissues within the body.

Many players were asymptomatic

Studies have included both symptomatic and asymptomatic players who tested positive for COVID-19. We know that, particularly in young people, the virus tends to cause mild or no symptoms, meaning players could be infected – and have cardiac involvement – without knowing they were infected.

This begs the question of whether all student-athletes should be screened for myocarditis, regardless of whether or not they had symptoms. And that opens up a much bigger discussion.

Mass cardiac MRI testing for athletes is impractical

Frankly, standardized advanced testing for heart issues for athletes might create more risks than benefits. For starters, MRI testing is expensive, and the technology is not particularly mobile. Student-athletes would have to travel or be transported to health centers regularly for testing. Then the questions become: Who pays for that? The school or the student's insurance?

Secondly, the test might reveal information that doesn't necessarily affect the student's ability to play sports but might be concerning to the student, their parents, or their coach.

What these studies tell me is that we need more research to inform the longitudinal analysis of heart damage caused by COVID-19. Will these student-athletes still have heart damage in five years, or 10, or 20? And how will it impact their livelihood? Might they benefit from cardioprotective medications? Time and research will tell.

Related reading: Can pre-competition ECG testing save young athletes’ lives?

Implications for non-athletes

Patients who aren’t considered elite athletes come to the hospital with COVID-19 and are screened for cardiac issues using EKG and troponin levels. We might assess a patient with MRI, for example, if they are recovering but still have an increased heart rate or shortness of breath that isn't explained by lung involvement.

Often, we find that these patients are deconditioned – their muscles have grown weak since they have been laid up with their illness. However, we will check the heart to ensure they get the care they need to recover.

In general, if an athlete or a patient is not feeling up to par after recovering from COVID-19, it is not safe for them to return to play. The same is true for seasonal respiratory infections that can affect the heart, including influenza. We typically recommend patients refrain from exercise, including hard labor, for at least a few weeks, and see their doctor for follow-up testing.

For athletes, and everybody else, the best thing to do is take it slow after recovering from COVID-19. In less than a year, the virus has proven itself to be unpredictable. Following your doctor’s recommendations closely as you increase activity and get safely back in the game.

To talk with a cardiologist about your cardiovascular health, call 214-645-8300 or request an appointment online.