Genetics and the heart: Using your family’s past to see into the future

June 22, 2015

Genetic testing is playing an increasing role in all fields of medicine these days, and that includes cardiology.

Here’s just one example of a woman with a serious heart problem and how we determined, through genetic testing, whether her daughter had inherited that problem. The story also offers a glimpse into a future of highly personalized treatment for people with heart disease. Perhaps it’s a story that has relevance to your own family.

Carmelita Vaughn is one of the most memorable patients I’ve worked with in recent years. She works in the Customer Service Department for the City of Irving, where, I hear, she fields questions and handles problems with efficiency and professionalism. Carmelita, 61, stays fit doing aerobics, and she tells me she’s active in her church and volunteer work.

Carmelita comes from a large family. Unfortunately, cardiomyopathy (deterioration of the heart muscle) and heart failure at an early age run in her family. In fact, many of her family members have died suddenly and unexpectedly. Carmelita was first treated for heart problems in 2005, when she was 51. Doctors implanted a defibrillator in her heart to detect abnormal rhythms and to shock her heart back into normal rhythm when needed.

A very weak heart

I first met Carmelita in November 2012, when she was referred to me following a number of problems. By that time, her heart was very weak.

In a heart that is working normally, 60 percent of the blood in the left ventricle, the main pumping chamber of the heart, is pumped out with each heartbeat. Carmelita’s heart was so weak that it was pumping less than 20 percent of the blood in her left ventricle.

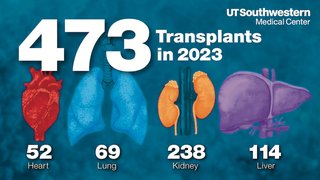

Her weak heart was causing her to have a lot of trouble breathing. After she told me about her relatives who had died suddenly, including one at a family barbecue, I did not think it was safe for her to leave my office and go home, so I admitted Carmelita to the hospital. We evaluated her and found that she would be a suitable candidate for a heart transplant. Finding a transplant match can be a difficult process and can take a long time, but Carmelita told me she knew she would be getting a new heart soon and that she wasn’t leaving until it happened.

She was correct in her strongly held optimism. Just 23 days after I admitted her, Carmelita walked out of the hospital with her new heart. She has done very well since then. She’s back to her volunteer activities and does aerobics two nights a week. In September 2014, she participated in the 3-mile Dallas Heart Walk

Would her daughter be affected?

But Mrs. Vaughn’s story doesn’t end with her successful transplant.

From the family history, it was clear there must be a genetic predisposition to a weakening of the heart muscle. I referred Carmelita to Dr. Helen Hobbs who does genetic testing of patients at UT Southwestern. My colleague looked at more than a dozen genes and found some genetic mutations that were likely associated with the family’s cardiomyopathy problems.

Carmelita’s daughter elected to be tested to see if she had some of the mutations in her genes that would make it likely for her to develop cardiomyopathy. Happily, she learned she had not inherited those mutations.

Therapies tailored to you

Identifying individuals who have inherited a propensity for cardiomyopathy is just a start to the advances genetics is bringing to cardiology.

In the future, genetic testing may allow us to tailor our medical therapies to a specific abnormality, rather than treating all patients with weakness of the heart with the same drugs. Potentially therapy tailored to a patient’s genetic makeup may mean that, someday, patients like Carmelita won’t be told they need a heart transplant.

That will be good news for patients – and equally welcome news for their children and grandchildren.

To schedule an appointment with Dr. Drazner or any of the heart specialists at UT Southwestern, call 214-645-8300.