Why lung transplant rejection is more normal – and treatable – than most think

October 11, 2018

Lung transplantation is at an all-time high in the U.S., with 2,449 procedures performed in 2017 for individuals with severe conditions such as interstitial lung disease, cystic fibrosis (CF), pulmonary hypertension, and emphysema. UT Southwestern is one of four medical institutions across the country that has annual survival rates that are better than the national average.

As the frequency of transplantation increases, we also need to increase education about transplant rejection (acute cellular rejection), which is more common than patients and families might think and treatable with specialized care.

In fact, acute cellular rejection of lung transplants occurs in up to 90 percent of patients. Rejection occurs when the body’s immune system creates antibodies that recognize and attack the new lung as if it were a foreign invader, similar to how the body would attack a virus. Acute rejection occurs with quick symptoms, while chronic rejection is more serious and affects about 10 percent of patients.

While chronic rejections typically can’t be reversed, acute rejections are very treatable. Many patients can even be treated at home with the care of a transplantation expert.

How lung transplant rejection is treated

Acute rejections

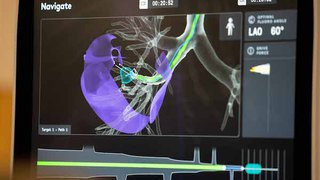

The first thing we see in patients having lung transplant rejection is decreased functionality of the lungs. We send every lung transplant recipient home with a spirometry machine, which is a device used twice a day to measure the amount of air they can exhale in one second. If the volume drops by more than 10 percent, we ask them to call their doctor so they can be evaluated.

During an evaluation, a doctor can confirm whether patients are experiencing lung rejection by performing a biopsy and looking for lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell that circulates in the blood and, in the case of rejection, attacks the blood vessels of the lungs. We rank the severity of the rejection on a scale of zero to four, with four being the most severe.

Patients who have a rejection score of three or four typically require treatment in the form of anti-rejection medication to trick the immune system into accepting the new lung. We usually begin with high doses of steroids that patients can take at home until the rejection reverses. If steroids aren’t effective, we turn to other treatment options, such as lympholitic medications.

To ensure patients don’t develop antibodies after lung transplantation, we screen for them each month during the first year, every three months the second year, and annually after that. If we see antibodies forming, we quickly treat the patient with plasma exchange. In this therapy, we draw patient’s blood, put it through a dialysis machine to remove the antibodies, and return the “clean” blood to the patient’s body.

Chronic rejections

When treatment for an acute lung rejection doesn’t work, the patient can develop chronic rejection of the new lung. This can lead to:

● Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS): The bronchioles are affected by thickening in the airway of the lungs, causing air to come in but not out (similar to asthma).

● Restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS): The lungs become smaller and smaller, causing difficulty with breathing because the patient cannot expand the lungs to breathe in air.

"Chronic rejections can’t usually be reversed; however, acute rejections are very treatable. Many of our treatments can be done at the hospital or at home, which is a relief for patients who’ve already had to go through a difficult lung transplant."

– Fernando Torres, M.D.

Does treatment affect the immune system?

Because antibodies play such a pivotal role in fighting off infections throughout the body, some patients wonder whether their immune system will change when antibodies are removed. The answer usually is no. By activating some lymphocytes called T-cells, the immune system is still able to respond to infections present throughout the body. For example, if someone develops chickenpox as a child, he or she will never get it again because T-cells are exposed to the chickenpox, become active, and create the antibodies to destroy the virus.

It’s no different for patients after acute lung rejection because they can still develop antibodies against infections. Also, we can provide patients with medications, such as antibiotics, to assist their immune system. Furthermore, we suggest patients avoid crowds of people, wear masks when they are out and about, and wash their hands frequently.

Advanced care and future treatment

At UT Southwestern, we study the process in which antibodies form against donors’ lungs. Our goal is to learn the most effective way to protect patients from antibodies and reduce the incidence of chronic lung rejections. The process starts by identifying patients’ antibodies and then putting patients on protocols in which we use medication to kill the cells that produce the antibodies. Then we monitor the patients over time, making sure the antibodies don’t recur. The protocol is unique, and we’ve been refining it since 2013.

Once a patient decides to pursue lung transplantation, it’s important to ensure that the medical center at which he or she has the transplant has high success rates and leading expertise to manage rejection symptoms.

Acute rejection is a normal and expected response to a new lung. Fortunately, with proper care many patients can recover and enjoy an improved quality of life with their new lungs.

Stay on top of health care news. Subscribe to our blog today.