‘Miracles do happen!’ Rare case of normal pressure hydrocephalus successfully treated

February 10, 2026

At age 66, Richard “Dick” Nash first suspected something might be wrong when he participated in a Dallas walk for juvenile diabetes in honor of his granddaughter. “It was only two miles – no big deal – but I wasn’t able to complete it without falling down,” he recalled. “My wife had to help me back to the car.”

After that day in 2011, Dick’s health continued to deteriorate. His legs would stiffen involuntarily, his sense of balance worsened, and walking became increasingly difficult, if not impossible. The speed of his physical movements became noticeably slower overall. Even trying to concentrate felt sluggish, making everyday communication a challenge.

Eventually he sought out a neurologist and was diagnosed in 2016 with Parkinson’s disease, a progressive, degenerative disorder with no clear cause and no cure. He began physical therapy and medication, hoping to regain some of his mobility and cognition.

But something didn’t feel right for Dick.

Even though he had the hallmark signs of Parkinson’s – stiffness, slow movement, poor balance, cognitive issues, incontinence – many of the treatments didn’t seem to make a difference. “The symptoms were never consistent,” he said.

Determined to find answers, Dick set out on a quest to regain his health. Fortunately, he had spent more than 10 years as an insurance agent and was familiar with navigating Medicare and the complex medical system. For the next several years, he cycled through numerous physicians and specialists.

Then his journey led him to UT Southwestern. There, doctors at the Peter O'Donnell Jr. Brain Institute identified the true culprit: normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), a rare condition caused by excess fluid accumulating in the brain.

With a dedicated team of NPH experts behind him, Dick underwent the surgery he needed to turn his health around. Within months of receiving the correct diagnosis, he's regained his physical independence, his ability to communicate more easily, and precious quality time with his family. What started as a grim outlook for the future has turned into a new beginning.

What is normal pressure hydrocephalus?

Typically seen in patients over age 60, NPH is characterized by an excess buildup of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the brain. A healthy body constantly creates CSF, cycles it through the brain, and reabsorbs it. When these processes are interrupted, extra fluid accumulates, compressing the brain and impairing its ability to clean itself. This can lead to progressive difficulties with:

- Mobility, particularly stiffness when walking

- Cognition, marked by sluggish thinking, confusion, and/or forgetfulness

- Urinary incontinence

Unlike typical hydrocephalus, where patients have a significant increase in pressure on the brain, patients with NPH show little or no pressure increases, making the condition harder to detect. Recent international studies suggest that NPH affects about 1.5% to 3% of patients aged 70–77, and more than 6% of those 80 and older, which is considerably higher than the estimated prevalence of Parkinson’s disease. That means as many as 1 to 2 million people in the U.S. may be living with NPH. Unfortunately, only about 20%-40% are ever diagnosed and receive treatment.

Types of normal pressure hydrocephalus

NPH is typically divided into two categories:

- Idiopathic NPH, where the exact cause is unknown but is usually attributed to aging issues that disrupt how CSF is circulated in the body

- Secondary NPH, where the CSF disruption can be traced to another medical condition such as:

- Head injury

- Surgery complications

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage (bleeding in the area around the brain)

- Brain tumors

- Brain infections (such as meningitis)

- Brain inflammation

NPH received a rare boost in the public spotlight in May 2025, when famed musician Billy Joel revealed his own diagnosis and began treatment.

NPH: A misunderstood form of dementia that can be reversed

- Padraig O'Suilleabhain, M.D.

- Jon White, M.D.

- Jeffrey Schaffert, Ph.D.

May 23, 2025

The search for effective treatment

In the years after Dick’s diagnosis of Parkinson’s, his illness became harder to manage. His leg stiffness worsened until he was mostly homebound. He needed a wheelchair anytime he left the house. His cognitive deficits also made it difficult for him to hold conversations or use the phone or a computer.

All this took a toll on his main caregiver, his wife of more than 55 years. “He had basically given up,” Sharon Nash said. “He didn't want to live. He didn't want to do anything, so his muscles had atrophied. He just was not motivated to care for himself.”

Fortunately for Dick, a routine visit to a physical therapist at UT Southwestern to help with his incontinence spurred the breakthrough he needed.

Like his previous health care practitioners, pelvic floor specialist Michelle Bradley, PT, DPT, WCS initially didn’t see any reason to doubt Dick’s Parkinson’s diagnosis. She began working with him to ease his symptoms. It wasn’t until Dick arrived for a later appointment in a wheelchair that she suspected something else might be going on. “He told me he had a procedure a couple of days earlier that required valium. Since then, he’d had great difficulty walking,” she said. “Knowing valium does not cause such a quick and long-lasting decline, I was concerned.”

The next time she saw Dick, his condition had worsened. Even for Parkinson’s, such a rapid change in a short period of time was unusual and raised a major red flag. “I was so concerned that I walked with him to the front and asked that Mr. Nash be scheduled with a neurology specialist as soon as possible,” she said.

For the first time in years, Dick felt someone truly saw what he was going through.

The first steps to an NPH diagnosis

Dick initially met with Vibhash Sharma, M.D., Medical Director of the Interventional (Neuromodulation) Movement Disorders Clinic at UT Southwestern. After a thorough evaluation, Dr. Sharma ruled out Parkinson’s.

Even though Dick’s legs would freeze up and cause him to fall, he had not developed other conditions consistent with the disease. His prescription for levodopa, a standard Parkinson’s medication that boosts dopamine levels in the brain, appeared to have no effect on his symptoms. A past DaT scan (Dopamine Transporter Scan) similarly failed to show strong evidence of Parkinson’s.

Based on a new MRI scan and his own clinical exam, Dr. Sharma referred Dick to the NPH group at UT Southwestern.

The right team for the right diagnosis

In February 2024, Dick had his first appointment with UT Southwestern’s dedicated NPH team. The interdisciplinary group includes Padraig O’Suilleabhain, M.D., a neurologist specializing in movement disorders, and Jeffrey Schaffert, Ph.D., a clinical neuropsychologist specializing in dementia syndromes.

While some neurologists encounter NPH through their clinical practice, UT Southwestern has taken a more focused approach by forming a dedicated interdisciplinary team to tackle potential NPH cases. By combining their expertise, the team members can identify subtle signs of NPH more easily in patients, streamline care, and hopefully bring clarity to a notoriously ambiguous condition.

Given Dick’s symptoms and past testing, the team was not particularly surprised that Dick had received a Parkinson’s diagnosis. As they set to work unraveling his extensive medical history and performing their own evaluations, however, they noted even more evidence of NPH.

Clinical symptoms

They studied his movements. “His walking difficulty had what we call ‘magnetic gait,’ where the tendency is for his feet to kind of stick to the ground as though there were magnets in his shoes,” Dr. O’Suilleabhain explained. “It’s a classic gait complaint, and it had deteriorated over the course of 10 years or so.”

His negative DaT scan and the fact that he hadn’t responded to levodopa concerned Dr. Schaffert. “If a patient gets a lot better [on levodopa], that would be more suggestive of Parkinson’s in many cases,” he said. “The fact that he didn't get better raises a yellow flag of ‘what else could we be dealing with?’”

Dick’s fluctuating symptoms also added to the potential evidence for a new diagnosis. “It's certainly common for people to feel their brain operating differently at times, both physically in terms of how they walk and cognitively in how clearly they're thinking,” Dr. O'Suilleabhain said. “Sleep, caffeine, blood pressure, and even the weather can have an effect. Parkinson’s symptoms can change in severity as neurons are lost, but the variation in CSF outflow that NPH causes produces a similar effect.”

Imaging

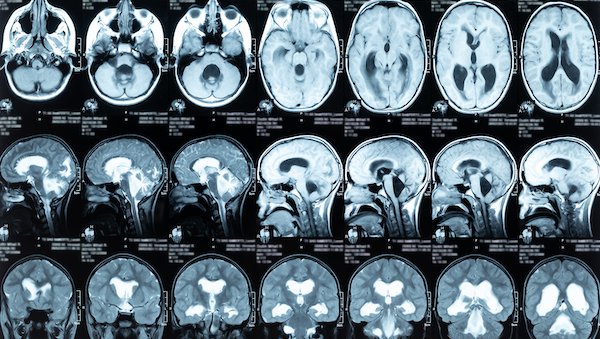

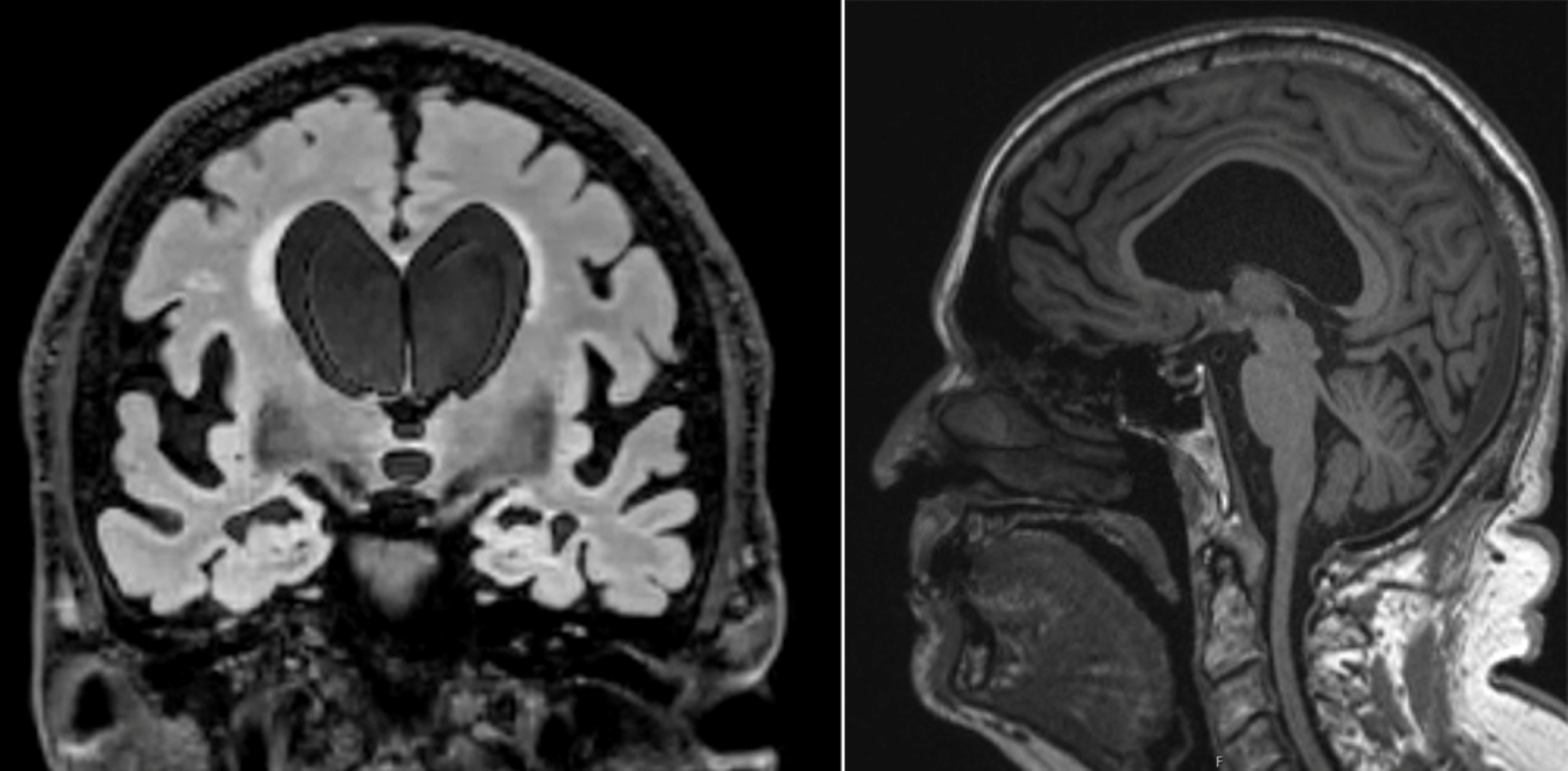

Based on his scans, the ventricles in the middle of Dick’s brain had enlarged a significant amount, likely caused by excess CSF and reduced outflow, which can disrupt communication between the brain and legs.

There also was evidence of disproportionately enlarged grooves in the brain, which happens when CSF is trapped in those spaces. On scans, this can look like brain shrinkage, which may have contributed to Dick’s earlier misdiagnosis.

CSF drains

One key detail the team noted was that Dick had already completed two lumbar spinal taps over the course of his illness. During these procedures, a small needle or catheter is inserted into the lower back to remove fluid around the spinal cord. Draining a large amount of CSF can sometimes relieve symptoms and aid in the diagnosis, although a lack of response does not rule out NPH. But for Dick, the results were inconclusive.

Two MRI scans for Dick Nash show some of the classic signs of NPH. The scan on the left taken from the front shows large ventricles, disproportionately enlarged subarachnoid spaces at the Sylvian fissures, and narrowing of the sulci at the vertex. In the side view on the right, the ventricle fluid space is enlarged and bowing upward, with narrowing of the corpus callosum.

The NPH diagnosis gap

Unfortunately for patients with NPH, initial misdiagnosis is common.

Unlike cognitive conditions that can be identified by certain markers, NPH lacks a definitive test (for example, brain scans of Alzheimer’s patients typically show a buildup of a protein called amyloid, which forms structures that disrupt normal brain functions). Multiple health issues can further muddy the waters. Patients typically undergo CSF testing, lumbar drains, medication, and potentially surgery before their physicians reach a definitive diagnosis of NPH.

The medical community seems to be catching on that NPH could be more prevalent than previously thought. Researchers in Sweden studying brain MRI scans from nearly 800 70-year-old patients found 1.5% with evidence of NPH (an earlier study also revealed a significantly higher prevalence among those over age 80).

This is one of the main reasons specialists at UT Southwestern have combined their expertise. “We're trying to be more systematic about how we make an NPH determination,” Dr. O'Suilleabhain said. While lumbar drains continue to be a factor in diagnosis, the team hopes to move away from such invasive testing to a more streamlined array of cognitive and mobility tests.

The team also hopes to improve methods for distinguishing NPH from other conditions and predict treatment response by analyzing proteins in CSF and blood. As principal investigator, Dr. Schaffert helped move the research program forward significantly by securing $1.2 million in funding: “We were able to leverage our clinical pathway into substantial research efforts. We look forward to launching more advanced imaging, biomarker collection, and longitudinal follow-up for our patients this year.”

One last test to confirm NPH

To help determine next steps, the NPH team proposed Dick undergo one more CSF drain along with a lumbar infusion test, a much more extensive diagnostic procedure not offered by many clinics.

Dick was admitted to William P. Clements Jr. University Hospital, where a lumbar drain was placed on him for four days straight. Every four hours, doctors would drain 20 milliliters of CSF, essentially removing half of what his body produced and forcing the brain’s fluid systems to reset. Dick reported some improvement, but like his previous drain tests, the results weren’t definitive.

During the same hospital visit, however, doctors also performed a lumbar infusion test, which uses real-time sensors to monitor intracranial pressure (ICP) and actively measure how well CSF flows and is absorbed by the brain. Dick’s ICP became elevated during infusion and took a significant amount of time to lower.

That result, along with imaging and clinical symptoms, provided enough evidence to diagnose Dick with NPH and support the recommendation of installing a shunt. There were no guarantees the shunt would help – and it would require surgery and possibly maintenance or replacement surgery down the road – but it was still the best chance for Dick to get back on his feet.

After discussing the procedure with neurosurgeon Jon White, M.D., a date was set.

Relieving the brain pressure

On Aug. 1, 2024, Dick arrived at the Clements University Hospital for surgery.

In Dick’s eyes, this was his last shot to regain the life he’d had before his illness. “I decided if this surgery didn’t work, I was going to declare hospice,” he said. After years of setbacks and uncertainty, he was ready to move forward or let go.

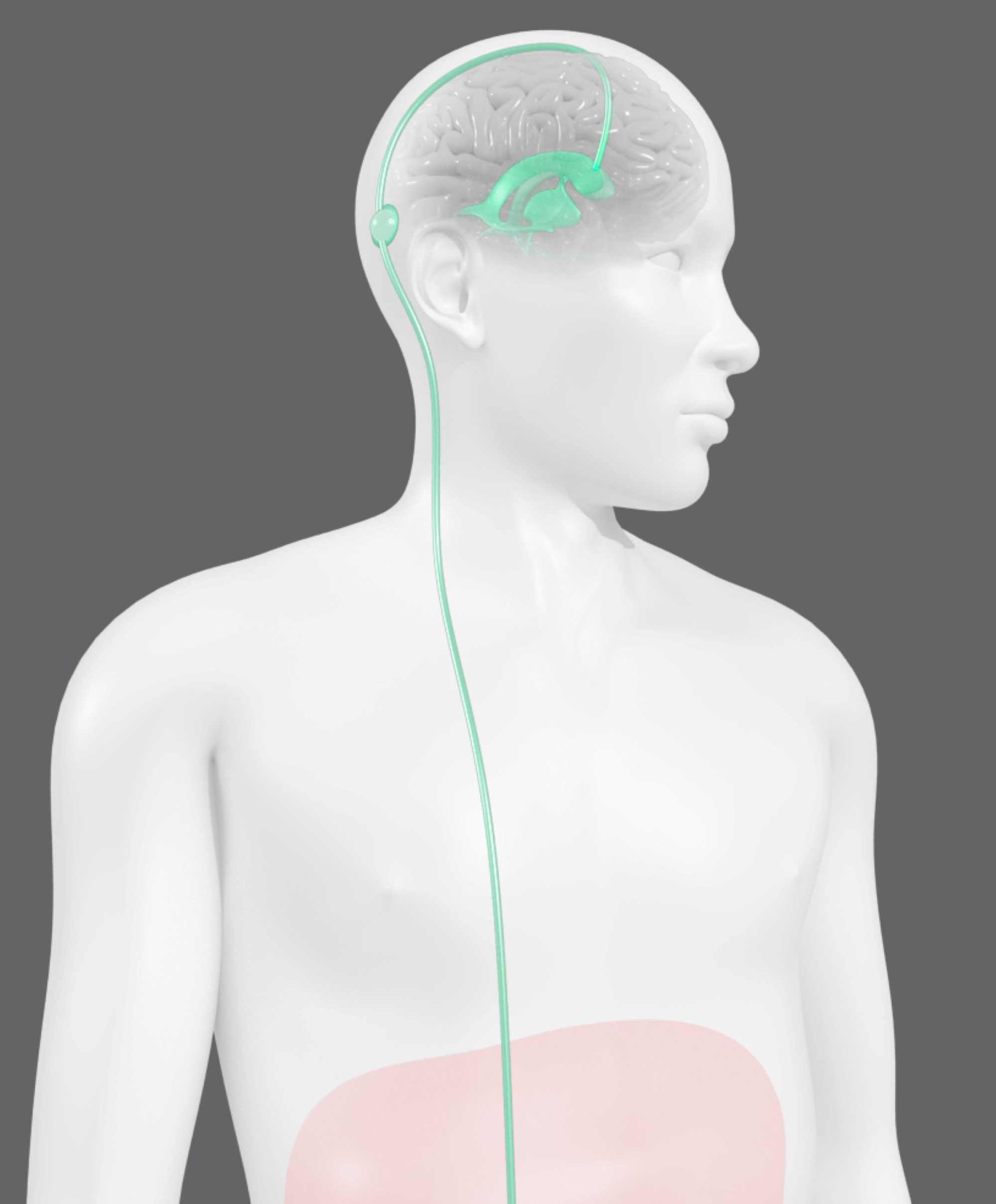

That day, Dick had two surgical teams – one to install a ventriculoperitoneal shunt into his skull and another to connect it to a drain in his abdomen. The shunt was inserted into the brain’s ventricles, where the fluid appeared to accumulate the most. For the second part of the procedure, a long, thin tube was connected to the shunt and threaded through his neck and chest to the peritoneal cavity, a space in the abdomen that houses digestive organs.

Once the procedures were completed, the shunt would act as a relief valve, opening to release CSF when the pressure in his ventricles got too high. The CSF would then flow down the tube into his abdomen to be absorbed by the body. Once the pressure returned to a normal range, the shunt would close again, stopping the flow of CSF. This way, the fluid pressure would stabilize, and the brain’s waste removal system would be restored.

Though shunts have been shown to improve functionality in NPH patients, their overall effects on cognition and mobility are still unclear. UT Southwestern recently participated in a randomized controlled clinical trial involving multiple sites in the U.S., Canada, and Sweden to test the effectiveness of shunting – the first trial of its kind in the world. By understanding its full effects, doctors hope to determine which patients are likely to benefit.

From NPH to rebirth

Most patients with NPH don’t see a significant difference for weeks or even months after a shunt is installed. For Dick, the change was almost immediate.

Just one day after surgery, he did something he hadn’t done in years: He got out of bed and counted as he took 250 steps with a walker. “It was the furthest I’d walked in six months,” Dick said. “I’d shown up for the surgery in a transport wheelchair, so walking that much was a big deal.” This was, quite literally, his biggest step forward in years.

Describing the surgery as his “day of rebirth,” Dick has been determined to stay healthy. More than one year later, he walks about three miles daily and has regained much of the functionality he thought he’d lost forever. At 80, he’s able to do more than he could almost 10 years ago. “I can operate in the kitchen now,” he said. “I can go out when people invite me to leave the house. Sharon and I go out when we want to see a movie.” The pair are even planning to travel internationally later this year.

As part of his recovery, Dick began speech therapy, which helped him regain the socializing he’d lost during his illness. According to Sharon, “One of the things that happens when you have an illness like he had is you become isolated. And the more isolated you become, the more cognitive deficits you develop. He’s just so much better. Now he’s able to converse with people and do a lot of things that he just wasn't able to do before his surgery and before the therapy.”

Other symptoms have faded, too, including the incontinence that inadvertently put him on the path to healing. “I don't wear what we call ‘traveling pants’ anymore,” Dick said. “I also reduced my medication by about 60% – got rid of a lot of pills I don't need anymore.”

Of everything he’s gained over the past year, though, the most meaningful has been moments with his family. He’s most proud of spending more quality time with his young great-grandsons and is grateful for those who helped him get there. “Dr. Schaffert, Dr. White, and Dr. O'Suilleabhain are heroes because they did what was necessary,” Dick said. “They listened to me.”

After his own experience, Dick said his main hope is that NPH will gain more recognition in the medical community, so others can get the treatment they need to regain their lives.

“Miracles do happen,” he said. “And I was the beneficiary of a miracle.”

To find out whether you or a loved one might benefit from advanced neurology care for NPH, call 214-645-8800 or request an appointment online.